Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1, 1932

Karen Wright

Wednesday 6 July 2016

Wednesday 6 July 2016

The major retrospective of Georgia O’Keeffe’s work that opened this week at Tate Modern in London is a rare opportunity for British viewers to engage with this revered American artist. In the same season as the opening of the Tate extension Switch House, this exhibition illuminates the gallery’s determination to provide new readings of old favourites. Curator Tanya Barson has spun a new tale of O’Keeffe, showing her as a progressive artist who was influenced by photography and not “merely an observational painter”. The inclusion of photography, while interesting, again shows a lack of confidence by the institution to let a singular medium prevail.

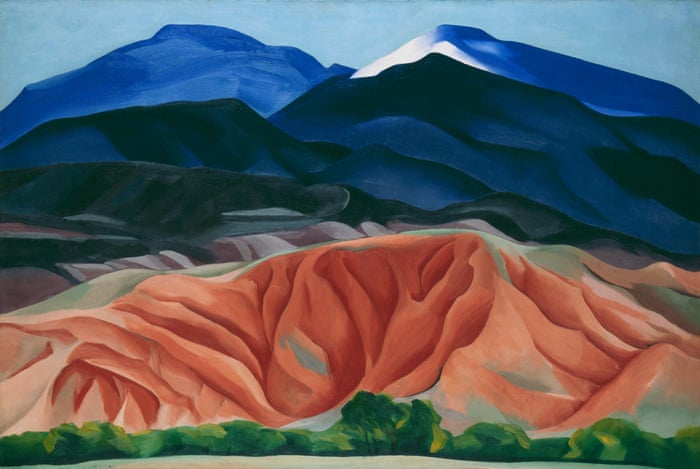

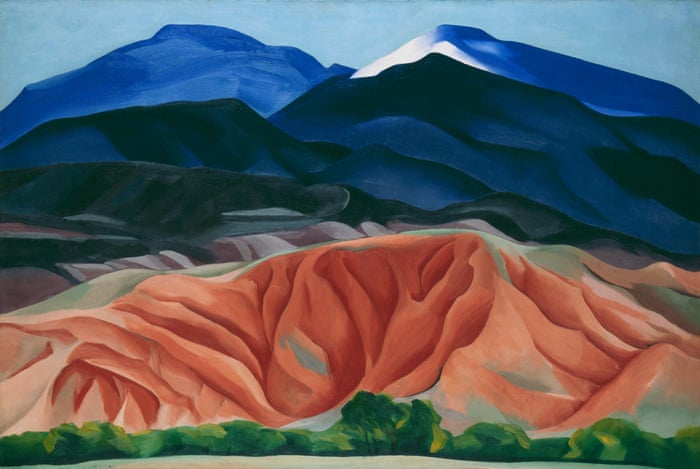

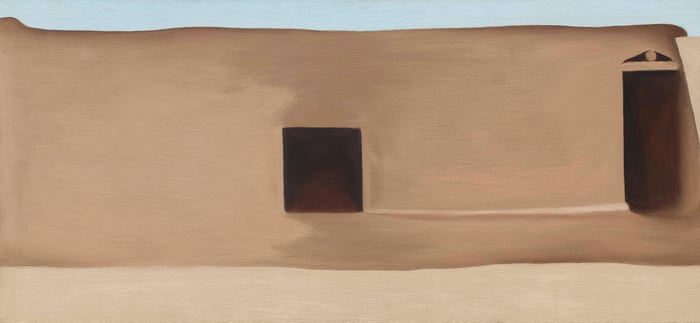

Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico / Out Back of Marie’s II , 1930

Georgia O'Keeffe was born in Wisconsin in 1887 and died in 1986 aged 98. Anyone who is lucky enough to live to be nearly 100 has experiences that span a great swath of history. O'Keeffe lived through two world wars, 17 US presidents, the Great Depression and the subsequent migration of east to west, as well as the great drought of the 1930s. She married the great photographer Alfred Steiglitz in 1924, for whom she was a muse, posing often for him clothed as well as in the nude. He also promoted O’Keeffe in both his own gallery as well as with his extensive circle of friends. Ironically, it was he who put forward the idea that the flowers were indeed eroticised images, a reading that O’Keeffe strenuously denied through her long life.

Black Mesa Landscape, New Mexico / Out Back of Marie’s II , 1930

Georgia O'Keeffe was born in Wisconsin in 1887 and died in 1986 aged 98. Anyone who is lucky enough to live to be nearly 100 has experiences that span a great swath of history. O'Keeffe lived through two world wars, 17 US presidents, the Great Depression and the subsequent migration of east to west, as well as the great drought of the 1930s. She married the great photographer Alfred Steiglitz in 1924, for whom she was a muse, posing often for him clothed as well as in the nude. He also promoted O’Keeffe in both his own gallery as well as with his extensive circle of friends. Ironically, it was he who put forward the idea that the flowers were indeed eroticised images, a reading that O’Keeffe strenuously denied through her long life.

Georgia O’Keeffe, shot for Vogue in 1967

I start with this context to remind viewers of the long history of over-looked women artists, not that O'Keeffe was one of these. The Museum of Modern Art in New York held a retrospective of her work in 1946. Her red poppies appeared on a US postage stamp, and her New Mexico home in Abiquiui, now open to the public, still attracts a pilgrimage of worshiping tourists, both female and male. Her best-known subject matter are the large and eye-catching flowers.

Grey Lines with Black, Blue and Yellow, 1923

O’Keeffe absorbed the landscape and language of her adopted home in New Mexico with a ferocity and a single mindedness, like that of Paul Cézanne when he painted and repainted Montagne Sainte-Victoire. Once when lost near Avignon I found that the soil of that mountain is that reddish brown seen and accepted as poetic licence in his great landscape paintings.

Grey Lines with Black, Blue and Yellow, 1923

O’Keeffe absorbed the landscape and language of her adopted home in New Mexico with a ferocity and a single mindedness, like that of Paul Cézanne when he painted and repainted Montagne Sainte-Victoire. Once when lost near Avignon I found that the soil of that mountain is that reddish brown seen and accepted as poetic licence in his great landscape paintings.

Abstraction White Rose, 1927

In this exhibition the paintings are arranged roughly chronologically and embrace her time spent in New York City, as well as in Lake George, where she spent summers during the early days of her marriage to Steiglitz. Her New York paintings, often created from a high perspective, encapsulate a city bathed in a dramatic night-time light. While her time spent in Lake George reflects her engagement with a verdant landscape; here, she wrote “I feel smothered with green”.

O’Keeffe was fiercely independent and continued to be so, well into her later years. She was a hiker, going “tramping” in all weathers, visiting and revisiting sites often remote from her home. This pioneering spirit led to her preoccupations with objects and views that she personally experienced.

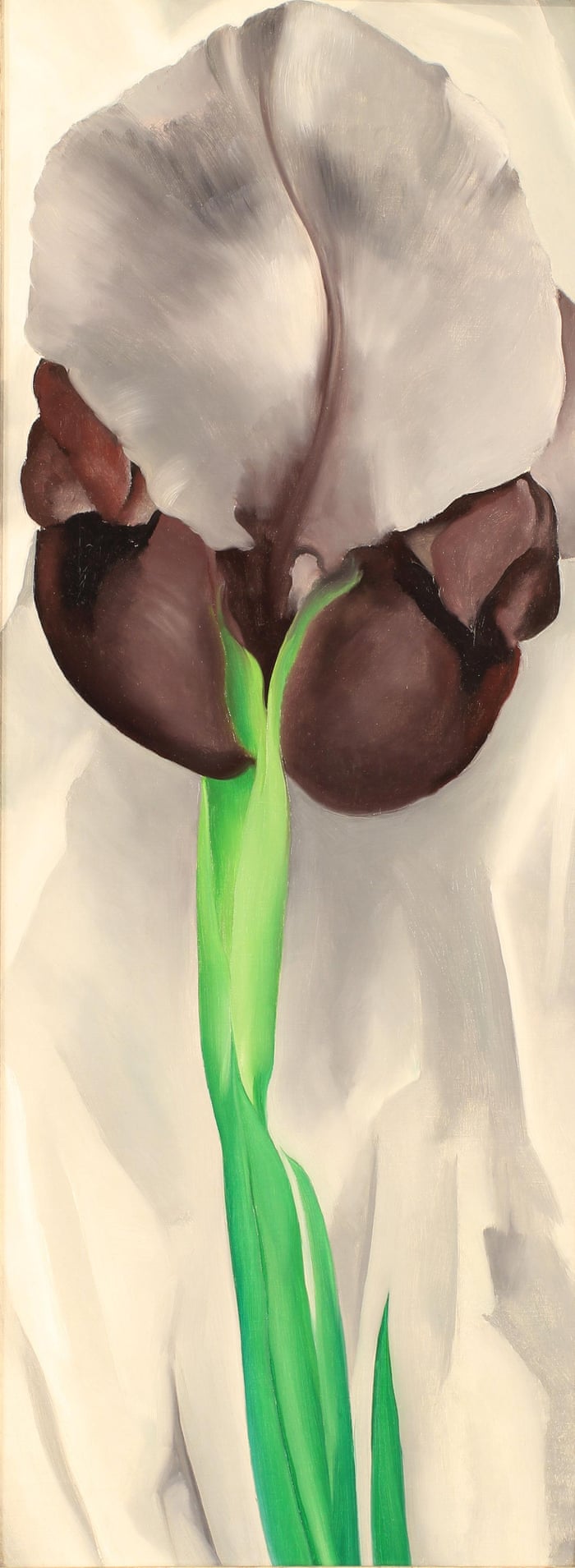

Dark Iris No 1, 1927

While O’Keeffe is best known for her flower paintings; closely observed blossoms. The room of these is sadly not the most powerful room here, perhaps due to loan restrictions. Some of the great blooms, including the luxurious purple iris, are not here, but there is her Jimson Weed of 1932, a painting that in 2014 became the most expensive ever sold at auction by a female artist when it was bought for $44.4m (£34.2m).

Black Place ll, 1945

Nearby are beautifully observed still lives, an eggplant, figs and an alligator pear in all their majestic simplicity. We are again told that these are a result of O’Keeffe looking at photography. I am not denying that O’Keeffe was friends with Paul Strand and Ansel Adams, as well as her relationship with Steiglitz; they did visit her and were inspired by the landscape that inspired her. But this is an artist who constantly reacted to locations with her own eyes.

From the Faraway, Nearby, 1937

O'Keeffe discovered Ghost Ranch – the property that was to become her home – in 1934, finally purchasing the house in 1940. The view from the ranch, a flat-topped mesa, became her favoured view. She painted and repainted it, saying at one point: “God told me if I painted it enough I could have it.” She also discovered the “Black Place”, another location she revisited throughout her life whilst driving through the Navajo country. These black hills, often abstracted into almost signs, recurred throughout her work became one of the locations of seriality-working through different permutations while also moving towards abstraction, the strong natural forms reduced into powerful symbols. A series of views of paintings of her front door marry the increasing abstraction of an artist such as Piet Mondrian with the observation of Claude Monet, quite a feat for a woman in the early 20th century.

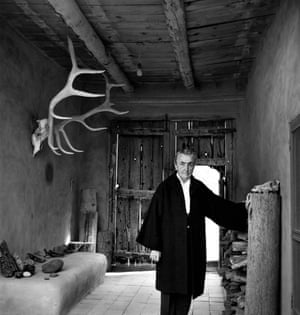

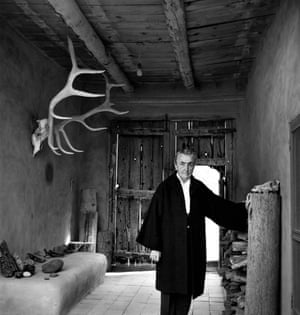

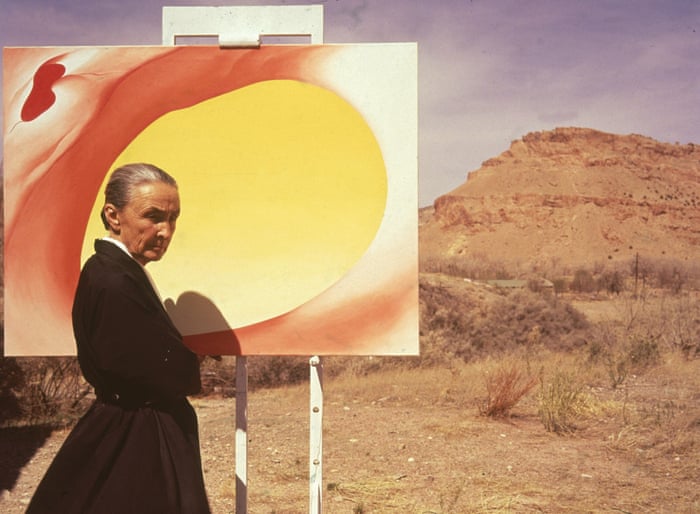

O’Keeffe in Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1960

Comparing these to Monet’s serial haystacks is an obvious connection, but I think that Mondrian’s voyage toward abstraction is more apposite. Mondrian’s trees of the early 20th century evolve into a different form of rigorous geometry, while O’Keeffe's sketchy paintings of cottonwood trees are aiming for a different essence of abstraction, one more akin to Canadian artist Emily Carr, who O’Keeffe met, and to the theosophy, serial and spiritual reading of Swedish artist Hilma af Klint.

Autumn Trees-The Maple 1924

I have been lucky enough to have visited the area where O’Keeffe worked and observed the wide skies and flatness of the landscapes. Walking in the arroyos, near her ranch, one discovers lying on the surface the sun-bleached skulls as well as artifacts of abandoned tribes. Not surprisingly, O’Keeffe was drawn to them, exploring and layering them along with other imagery, and some of these paintings look just wrong. Mule’s Skull with Pink Poinsetta (1936), an odd painting, reflects O’Keeffe's continued exploration of themes mashed and layered together. A group of depictions of native American dolls, Kachinas, sit strangely ill at ease with the landscapes ranged nearby. O’Keeffe travelled to Mexico to meet Frida Kahlo, who collected votive paintings, and Diego Rivera, and this group seems to mirror this interest.

New York Street with Moon, 1925

O’Keeffe was perhaps the first artist to paint the view seen from an airplane; her aerial shots of fluffy clouds and the horizontality of the sky produced from memories of her flights from New York City to Santa Fe. Again this is credited to her husband’s photographs of the sky and clouds, but when you stand in front of her Sky Above the Clouds III you can see the painterly licence that O’Keeffe adopted, making this painting much more memorable then the Steiglitz photographs, lovely though they are.

Georgia O’Keeffe photographed by Ansel Adams in 1937

Comparing these to Monet’s serial haystacks is an obvious connection, but I think that Mondrian’s voyage toward abstraction is more apposite. Mondrian’s trees of the early 20th century evolve into a different form of rigorous geometry, while O’Keeffe's sketchy paintings of cottonwood trees are aiming for a different essence of abstraction, one more akin to Canadian artist Emily Carr, who O’Keeffe met, and to the theosophy, serial and spiritual reading of Swedish artist Hilma af Klint.

Autumn Trees-The Maple 1924

I have been lucky enough to have visited the area where O’Keeffe worked and observed the wide skies and flatness of the landscapes. Walking in the arroyos, near her ranch, one discovers lying on the surface the sun-bleached skulls as well as artifacts of abandoned tribes. Not surprisingly, O’Keeffe was drawn to them, exploring and layering them along with other imagery, and some of these paintings look just wrong. Mule’s Skull with Pink Poinsetta (1936), an odd painting, reflects O’Keeffe's continued exploration of themes mashed and layered together. A group of depictions of native American dolls, Kachinas, sit strangely ill at ease with the landscapes ranged nearby. O’Keeffe travelled to Mexico to meet Frida Kahlo, who collected votive paintings, and Diego Rivera, and this group seems to mirror this interest.

New York Street with Moon, 1925

O’Keeffe was perhaps the first artist to paint the view seen from an airplane; her aerial shots of fluffy clouds and the horizontality of the sky produced from memories of her flights from New York City to Santa Fe. Again this is credited to her husband’s photographs of the sky and clouds, but when you stand in front of her Sky Above the Clouds III you can see the painterly licence that O’Keeffe adopted, making this painting much more memorable then the Steiglitz photographs, lovely though they are.

Georgia O’Keeffe photographed by Ansel Adams in 1937

There are many criteria as to what makes an artist great and one is how influential their work is on others. There is no doubt that the American painter Agnes Martin looked closely at O’Keeffe. It is not just their physical proximity (Martin landed in Taos when she moved west from New York City); it is the reaction to the rigorous landscape of place and the strong horizontality of the land and the sky. I was once told an anecdotal story about Martin that she always painted with the lines running down to avoid drips, but then displayed them horizontally.

From the River – Pale, 1959

This is an extraordinary show, a collection of nearly 100 works celebrating a woman artist, long overdue in this country, the last being in 1993 at the Hayward in London. Why do I feel churlish? Perhaps because in trying to make O’Keeffe seem progressive there is the constant intervention of male artists – even great ones – that seem unnecessary.

Oriental Poppies, 1927

Georgia O’Keeffe was a role model for many women artists. One could say there was a man behind her early success – Steiglitz did as much as he could for his muse, though she lived apart from him for many years. She was a woman who plowed her own furrow and this is clear in the haunting and revealing portrait of O’Keeffe by Anselm Adams taken in 1937 from the back, the perspective of sky and land and horizon spread out in front of her. I think that a quote from her sums up this rewarding if flawed exhibition: “A woman who has lived many things and who sees lines and colours as an expression of living might say something that a man can’t – I feel there is something unexplored about women that only a woman can explore – the men have done all they can do about it.”

The Georgia O'Keeffe exhibition continues at Tate Modern in London until 5 October.

No comments:

Post a Comment