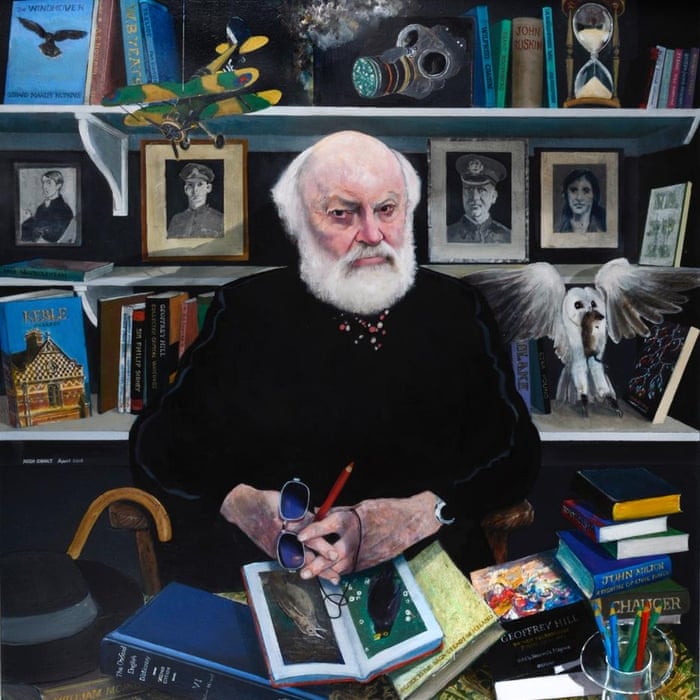

Sir Geoffrey Hill by Keith Grant, 2015

Poet and academic with a passion for the history and landscapes of England

Sir Geoffrey Hill captured in a portrait by Keith Grant, 2015. Photograph: Chris Beetles Gallery

Robert Potts

Friday 1 July 2016

Sir Geoffrey Hill, who has died aged 84, was one of Britain’s finest poets in the second half of the 20th century. His was among the handful of names discussed in relation to the poet laureateship in Britain in 1998, after the death of Ted Hughes; and while it is hard to imagine Hill accepting such a dubious honour, or the post being awarded to so demanding a poet, he would not have been an inappropriate choice.

Hill had an unusually powerful sense of, and care for, the history of England; a sense above all of its bloody battles, religious schisms and civic institutions, and of its landscapes, especially those of his childhood. In his prose poem, Mercian Hymns, he conflated his Midlands childhood with King Offa’s Mercia, identifying his own birthplace as that of modern England.

Born in Bromsgrove, Worcestershire, Geoffrey was the son of William, a village policeman, and his wife, Hilda. “If you stood at the top of the field opposite our house,” he once recalled, “you looked right across the Severn Valley to the Clee hills and the Welsh hills very faint and far off behind them.”

Hill identified himself as working-class – indeed was “glad and proud to have been born into the English working-class” – and commemorated his maternal grandmother, who had spent her life making nails, in poem XXV of Mercian Hymns: “I speak this in memory of my grandmother, whose childhood and prime womanhood were spent in the nailer’s darg ... It is one thing to celebrate the ‘quick forge’, another to cradle a face hare-lipped by the searing wire.” Critics who accused Hill of nostalgia, conservativism, and reactionary and monarchist politics tended to ignore or misunderstand his passionate care for the nameless and forgotten victims of power, across all countries and all centuries.

Educated at Bromsgrove county high school, Hill was an excellent student, and – although “somewhat apart”, in the words of Norman Rea, a contemporary – played football, acted in school plays, and became a prefect. One of his roles was to introduce a piece of classical music in each morning assembly. As Rea recalled years later, it was a task he performed “with enjoyment and aplomb ... He demurred only once, in a stage-managed gesture, when he felt that to introduce Danny Kaye’s Tubby the Tuba, even for educational ends, was rather beneath him. With a sudden, winning smile, he delegated that task to the headmaster.”

Hill went on to Keble College, Oxford, where he read English, gaining a first (1953). Subsequently he taught at Leeds, being elected to a professorship in 1976, and then at Cambridge, where he was a fellow of Emmanuel College (1981-88).

At Oxford, he met the American poet Donald Hall, who told Hill that he was taking over the editorship of the Fantasy Poets and asked him to submit a manuscript. Later, Hall recalled receiving the poems: “I could not believe it. You can imagine reading these poems suddenly in 1952. I read them and I was amazed. I remember waking up in the night, putting on the light and reading them again. Of course I published them.”

The volume was For the Unfallen. It remains a powerful book, astonishing as a young man’s debut; ornate, rhetorical, grandiose in its subjects and themes. Genesis, the very first poem, takes the creation myth as its own creative occasion, beginning: “Against the burly air I strode, / crying the miracles of God” and ending:

By blood we live, the hot, the cold,

To ravage and redeem the world,

There is no bloodless myth will hold.

And by Christ’s blood are men made

free

Though in close shrouds their bodies

lie

Under the rough pelt of the sea;

Though Earth has rolled beneath her

weight

The bones that cannot bear the light.

For the Unfallen, eventually published in 1959, and all Hill’s subsequent books, dwell on blood and religion; his treatments of violence range from Funeral Music (from King Log, 1968), a remarkable sequence on the astonishingly violent battles of the Wars of the Roses, to his careful and sensitive elegies for Holocaust victims. From his earliest poetry he was intensely interested in martyrs, whether of the religious controversies of the 16th and 17th centuries, or totalitarian regimes of the 20th; and he aimed at a scrupulous weighing of the appropriate words by which their witness could be mediated. By making historical atrocities more immediate, and refusing to abandon the memory of the dead, Hill was also tacitly calling attention to more contemporary political predicaments.

His poetry was deliberately unfashionable – Hill emerged at the same time as the Movement poets, writers such as Philip Larkin and Kingsley Amis, and the contrast between them could not have been greater. Hill’s work was steeped in history (and occasionally myth), unashamed of intellectual and scholarly breadth; Movement poetry was cautious, rooted in a defiantly ordinary contemporary English postwar vision, scornful of “pretension”.

Nonetheless, Hill’s beautifully cadenced verse, with a recondite vocabulary enjoyable for its very strangeness, was unignorable, and he found a place in anthologies throughout the years.

He also published three volumes of essays, The Lords of Limit, The Enemy’s Country, and Style and Faith (all included in the Collected Critical Writings of Geoffrey Hill, 2008), which are object lessons in the importance of scrupulous reading, and equally scrupulous writing. His essay on Ezra Pound’s fascist broadcasts, My Word Is My Bond, is a highly significant rendering of Hill’s own ethic, and manages to be both rigorous and sympathetic in its judgments.

By the time his Collected Poems were published in 1985, the blurb in the Penguin edition confidently presented the polarised judgments on Hill alongside each other, commenting that Hill had generally “encountered either baffled goodwill or baffled resentment”. There were sympathetic commentators – Christopher Ricks, for many years, and Peter Robinson – who gathered together intelligent, informed appreciations of work that required a certain amount of research and exegesis for its proper appreciation. Hill could be a distant, exacting, curmudgeonly and sometimes ungrateful figure in those days, even to those who wished him well; though he also had unswervingly loyal relationships with friends such as RS Thomas and David Wright.

Illness, and a period of poetic inactivity, preceded Hill’s move to Boston in the US in 1988 to teach theology and English literature. He did not publish another book until Canaan in 1996, after which the books poured from him. He returned to England in 2006.

In his last years, when volumes came so much faster, Hill professed himself amazed at his youthful patience. From the 1950s to the 1980s, Hill might work at a phrase for weeks; but having had a heart attack in the late 1980s (and again in 2001), he had begun to feel, in his own words, “If I don’t do it now, I never will: there is that sort of urgency.”

After he went to the US, he was diagnosed as having suffered, since childhood, from chronic depression, and “various exhausting obsessive-compulsive disorders”; and the prescription of Prozac transformed his life. Hill had, in his critical work, written with sympathy and tact of the religious writers who suffered from neurasthenic difficulties, and later was quite open about his own case, speaking about it in interview, and in the poems.

Prozac he described as “a signal / mystery, mercy, of these latter days”. Another factor in his eventual happiness was surely his marriage in 1987 to Alice Goodman. With her, he had a daughter, Alberta; he also had four children, Julian, Andrew, Jeremy and Bethany, from his first marriage, to Nancy Whittaker, which had ended in divorce.

Goodman was the librettist of John Adams’s operas Nixon in China and The Death of Klinghoffer. In 1990, she was received into the Church of England, and in 2001 was ordained as an Anglican priest. Hill described his wife as one of the few people whose comments on his work he would always listen to – “99% of the time she’s right” – and introduced Hill to some diverse and surprising influences, such as the poet Frank O’Hara and the choreographer and dancer Mark Morris, whom Hill startlingly compared to Dryden. In Speech! Speech! there are a handful of subtle, tender lines that are surely addressed to his wife, and about his happiness: “Ageing, I am happy ... Togetherness after 16 years? You’re on.”

Hill’s last work had a mixed reception. The quartet of books from Canaan to The Orchards of Syon (2002) constitute a modern Pilgrim’s Progress, Hill’s epic conflation of autobiography, theology and history, rendered in defiantly modernist style and startling in its juxtapositions of the contemporary and the eternal. It is work that will undoubtedly take a great deal of time and a collaboration of commentators and critics to fully appreciate; but in its extent and ambition, and its ethical commitment, it already stands out amid the typical English poetry of its time. It seems certain that his work will survive long after the work of more fashionable poets has faded from view.

As professor of poetry at Oxford (2010-15), Hill delivered 15 lectures on writers from Shakespeare to Larkin, occasionally making sharp remarks about the state of contemporary poetry and the current poet laureate, Carol Ann Duffy. He was knighted in 2012.

He continued to write – he had a lead essay in the Times Literary Supplement in March this year, on Charles Williams. For the first time in 40 years, he had also begun to play the piano.

He is survived by Alice and his children.

• Geoffrey William Hill, poet and academic, born 18 June 1932; died 30 June 2016

Here's a review of Hill's Broken Hierarchies (2014) by Terry Kelly:

No comments:

Post a Comment