In the wake of a personal tragedy, Hockney embarked on a new project: to capture his wide social circle in defiantly exuberant tones

Tim Barringer

Friday 17 June 2016

David Hockney once said that art comes in three kinds – landscapes, portraits and still-lifes. This mischievous pronouncement was directed with a wry smile at the high priests of the contemporary art world, where the smart money is on conceptual art, installation, performance, video, and digital art. In a career spanning more than six decades, Hockney has experimented with photography and collage; he was a pioneer in the use of digital media and is a virtuoso of the iPad. Yet at the core of his practice lie the most traditional categories of British painting: landscape and portraiture, with an occasional still‑life thrown in for light relief.

In 2005, Hockney moved from California, where he had spent much of his adult life, back to live in Bridlington and the house where his mother, Laura, lived until her death, at 98, in 1999. When the prodigal son returned to his native Yorkshire, the results were electric. He produced a vast, euphoric body of landscapes employing a saturated palette of colours tinged with memories of the sunshine of the Hollywood Hills. A hugely successful exhibition at the Royal Academy in 2012, titled A Bigger Picture, placed the seal of public – if not unanimously of critical – approval on this rich new vein of creativity. The Yorkshire paintings suggested that Hockney, like Titian or Picasso, had developed a late style, arriving at a culminating mastery of his materials. The show cemented his status as a living national treasure, a successor to Turner and Constable, but one who, against all the odds, retained the cheeky irreverence of the bleached-blond celebrity of the swinging 60s.

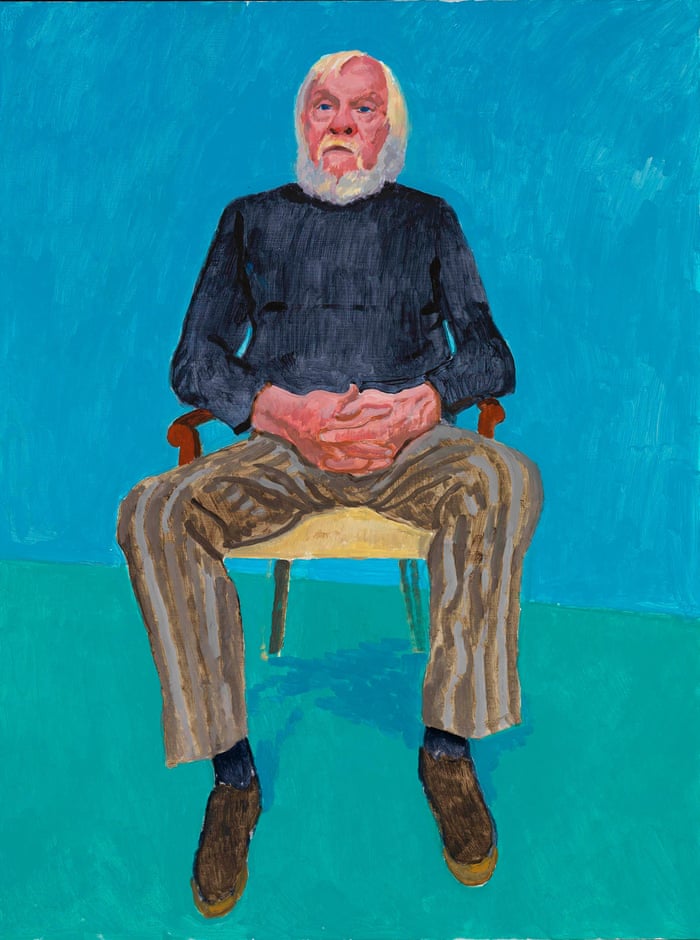

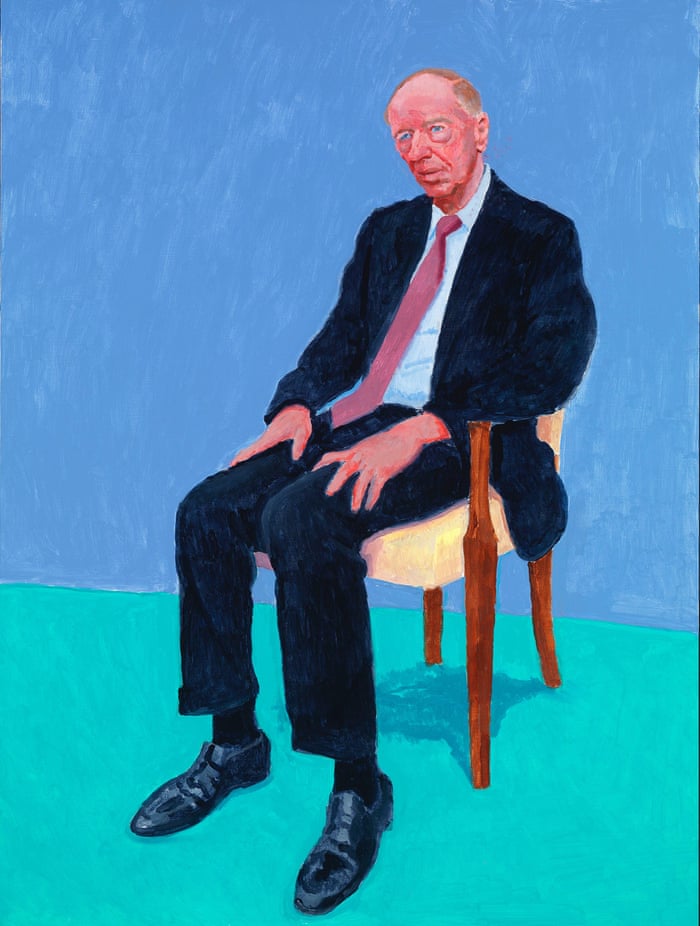

John Baldessari, 13th, 16th December 2013.

In 2013 Hockney suffered a minor stroke, and it seemed possible that his career, subject to so many reinventions over the years, might be entering its twilight; in the spring of that year, moreover, personal tragedy intervened with the accidental death of a studio assistant, Dominic Elliott. This cast a profound shadow over Hockney’s close-knit, quasi-familial studio team. Deeply affected, Hockney found himself unable to paint or draw for several months. He moved back to California, abandoning the Bridlington studio and ending the landscape project it had nurtured.

In the depths of this artistic and personal crisis, Hockney suddenly produced a portrait of Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima, his trusted studio assistant and amanuensis over many years. Head in hands, J-P (as Hockney calls him) appears a broken man, touched as strongly as the artist himself by the death of their young friend and collaborator. For Hockney the painting is “almost a self-portrait”: there is no mistaking the gravity of shared feeling that links old master and trusted lieutenant.

The portrait might have been allowed to stand alone as an elegy, a meditation on the fragility of life. But Hockney’s response was characteristically contrarian. Rather than an ending, it became a beginning. The upright format, its bright Californian colours contrasting painfully with the brooding quality of the figure, sparked new possibilities in the painter’s mind. From this personal, confessional utterance, there emerged a new project, grand in scale, public in scope. Portraits began to appear, each on an upright canvas 48 x 36 inches in size, tumbling out of Hockney’s Los Angeles studio in a headlong rush of productivity. Eventually the comprehensive portrait gallery of his wide circle of friends and acquaintances became the exhibition 82 Portraits and 1 Still‑life, which opens at the Royal Academy in London on 2 July.

These new portraits bring to fruition a project begun in Hockney’s adolescence and pursued ever since. His first portraits were, inevitably, of subjects near at hand. An early self-portrait sees the teenage artist in 1954 with a pudding-bowl haircut, sitting on a chair and staring awkwardly into the mirror. The only hint of incipient dandyism is a pair of flamboyantly striped trousers and a matching tie, whose pattern is wittily echoed in the yellow wallpaper.

Throughout his career, Hockney has repeatedly portrayed the same sitters – his parents (and especially his mother), friends, lovers, studio assistants – producing a family album in which a wide public can share. At moments of personal crisis – the collapse of major relationships, or the Aids epidemic of the late 80s – portraiture has provided him with solace, an opportunity to gather friends together, as well as technical exercise of the utmost difficulty. Hockney turns to portraiture as a great pianist may turn to Bach: it is the centre of his art and of his being.

Celia Birtwell, 31st August, 1st, 2nd September, 2015.

Celia Birtwell, 31st August, 1st, 2nd September, 2015.

In 2013 Hockney suffered a minor stroke, and it seemed possible that his career, subject to so many reinventions over the years, might be entering its twilight; in the spring of that year, moreover, personal tragedy intervened with the accidental death of a studio assistant, Dominic Elliott. This cast a profound shadow over Hockney’s close-knit, quasi-familial studio team. Deeply affected, Hockney found himself unable to paint or draw for several months. He moved back to California, abandoning the Bridlington studio and ending the landscape project it had nurtured.

In the depths of this artistic and personal crisis, Hockney suddenly produced a portrait of Jean-Pierre Gonçalves de Lima, his trusted studio assistant and amanuensis over many years. Head in hands, J-P (as Hockney calls him) appears a broken man, touched as strongly as the artist himself by the death of their young friend and collaborator. For Hockney the painting is “almost a self-portrait”: there is no mistaking the gravity of shared feeling that links old master and trusted lieutenant.

The portrait might have been allowed to stand alone as an elegy, a meditation on the fragility of life. But Hockney’s response was characteristically contrarian. Rather than an ending, it became a beginning. The upright format, its bright Californian colours contrasting painfully with the brooding quality of the figure, sparked new possibilities in the painter’s mind. From this personal, confessional utterance, there emerged a new project, grand in scale, public in scope. Portraits began to appear, each on an upright canvas 48 x 36 inches in size, tumbling out of Hockney’s Los Angeles studio in a headlong rush of productivity. Eventually the comprehensive portrait gallery of his wide circle of friends and acquaintances became the exhibition 82 Portraits and 1 Still‑life, which opens at the Royal Academy in London on 2 July.

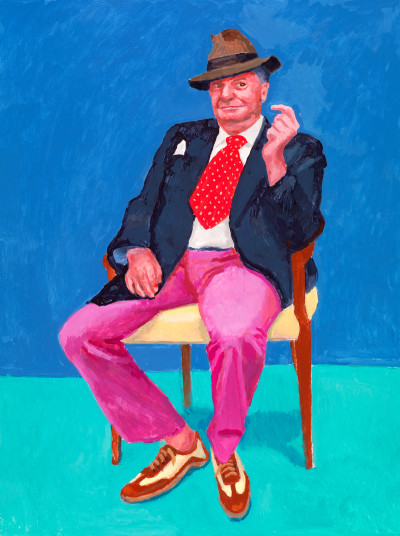

Barry Humphries, 26-28 Mar 2015

These new portraits bring to fruition a project begun in Hockney’s adolescence and pursued ever since. His first portraits were, inevitably, of subjects near at hand. An early self-portrait sees the teenage artist in 1954 with a pudding-bowl haircut, sitting on a chair and staring awkwardly into the mirror. The only hint of incipient dandyism is a pair of flamboyantly striped trousers and a matching tie, whose pattern is wittily echoed in the yellow wallpaper.

Throughout his career, Hockney has repeatedly portrayed the same sitters – his parents (and especially his mother), friends, lovers, studio assistants – producing a family album in which a wide public can share. At moments of personal crisis – the collapse of major relationships, or the Aids epidemic of the late 80s – portraiture has provided him with solace, an opportunity to gather friends together, as well as technical exercise of the utmost difficulty. Hockney turns to portraiture as a great pianist may turn to Bach: it is the centre of his art and of his being.

Hockney made a splash from his student days: indeed, his professional debut has become the stuff of legend. Anxious to overturn convention, at this time he professed to be wary of the portrait as a genre. Nonetheless, in DollBoy (1961) a student work of exceptional originality, he created a coded celebrity portrait, queering and subverting the medium in the process. Flowing from his crush on Cliff Richard, the painting has the improvised and hasty quality of erotic graffiti scribbled on a lavatory wall. At a time when homosexual acts were still illegal, Hockney found in the portrait a place to celebrate male-male desire.

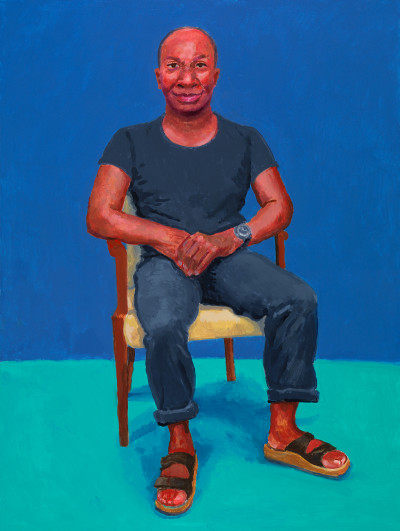

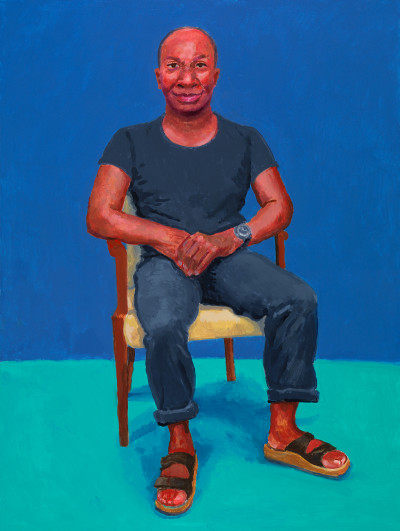

Earl Simms, 29th February, 1st, 2nd March, 2016.

By the 70s, Hockney had swerved back into an opulent vein of representational art closely linked to photography. His most famous portrait, Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy (1971), lies in the tradition of the conversation piece, in which leisured figures inhabit an interior or landscape. This work derives from personal affection: it depicts Hockney’s close friends, the fashion designer Ossie Clark and his wife, the textile designer Celia Birtwell. We stand where the artist stood, the third element in a triangular relationship. All three were from the north of England, and were darlings of fashionable society. Ossie, who died in 1996, despite international success as a designer drifted into a life of substance abuse that destroyed the marriage and left him a marginalised, lonely figure. Celia, by contrast, has remained a confidante of Hockney’s and has sat for him regularly for five decades. Her portrait is among the most vibrant works in the present exhibition: a grandmother and in her mid 70s, she mesmerises the painter now as always. This is one of his very few close relationships with women beyond his family: as he recently remarked, “we just laugh and laugh – even though she doesn’t always like the way I paint her”.

Birtwell has become familiar with Hockney’s rigorous portrait practices. The sitter arrives at the studio and is seated in a simple dining chair, which is raised up on a platform about three feet from the ground. Each sitter wears everyday clothes. Once the pose is agreed, one of the artist’s assistants will draw an outline around the sitter’s shoes so that work can be resumed with the sitter properly placed after breaks. Always working in silence, Hockney spends the first hour or so making a charcoal drawing. This establishes a likeness, focusing mainly on the face and hands. Drawing, he insists, lies at the core of portraiture: “I accept what I’ve drawn, and I get that in the first hour: by then, I’ve caught their individuality as they sit in the chair. Everybody sits in a different way.” Painting then continues over three days, with sessions of up to seven hours per day, with a break for lunch.

Earl Simms, 29th February, 1st, 2nd March, 2016.

By the 70s, Hockney had swerved back into an opulent vein of representational art closely linked to photography. His most famous portrait, Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy (1971), lies in the tradition of the conversation piece, in which leisured figures inhabit an interior or landscape. This work derives from personal affection: it depicts Hockney’s close friends, the fashion designer Ossie Clark and his wife, the textile designer Celia Birtwell. We stand where the artist stood, the third element in a triangular relationship. All three were from the north of England, and were darlings of fashionable society. Ossie, who died in 1996, despite international success as a designer drifted into a life of substance abuse that destroyed the marriage and left him a marginalised, lonely figure. Celia, by contrast, has remained a confidante of Hockney’s and has sat for him regularly for five decades. Her portrait is among the most vibrant works in the present exhibition: a grandmother and in her mid 70s, she mesmerises the painter now as always. This is one of his very few close relationships with women beyond his family: as he recently remarked, “we just laugh and laugh – even though she doesn’t always like the way I paint her”.

Birtwell has become familiar with Hockney’s rigorous portrait practices. The sitter arrives at the studio and is seated in a simple dining chair, which is raised up on a platform about three feet from the ground. Each sitter wears everyday clothes. Once the pose is agreed, one of the artist’s assistants will draw an outline around the sitter’s shoes so that work can be resumed with the sitter properly placed after breaks. Always working in silence, Hockney spends the first hour or so making a charcoal drawing. This establishes a likeness, focusing mainly on the face and hands. Drawing, he insists, lies at the core of portraiture: “I accept what I’ve drawn, and I get that in the first hour: by then, I’ve caught their individuality as they sit in the chair. Everybody sits in a different way.” Painting then continues over three days, with sessions of up to seven hours per day, with a break for lunch.

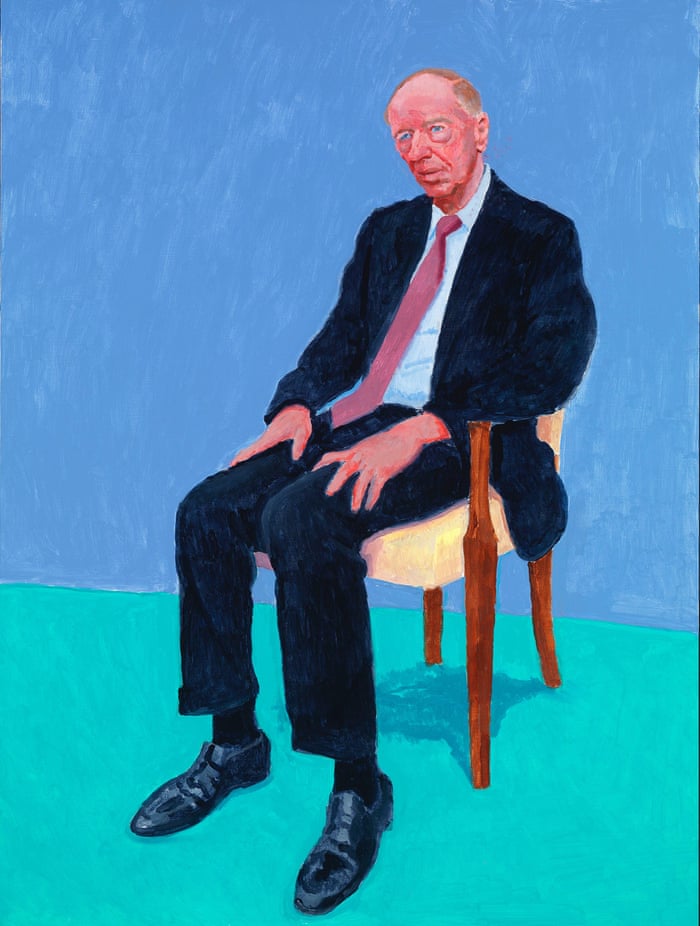

Lord Jacob Rothschild (2015)

A few sitters, such as philanthropist and collector Jacob Rothschild, whose schedules did not allow them to stay for the full period, were portrayed more quickly. Hockney is not averse to having a little fun with his sitters: Rothschild, lanky and quizzical, looks too tall for the chair; Barry Humphries sports a magnificently louche tie and pink trousers, a burlesque facade that masks his other identity as an astute patron and critic of art. More simple and heartfelt are the representations of Hockney’s family – his sister, Margaret, still in Bridlington, and brother John, who emigrated to Australia. A poignant absence is that of his mother and father, scrutinised so closely in earlier years.

Margaret Hockney (2015)

Margaret Hockney (2015)

Throughout the exhibition a benign atmosphere prevails, as if the tragedy of Elliott’s death can be assuaged only by a celebration of life. Perhaps the most significant encounter for Hockney came with a visit to LA by the artist Tacita Dean, her husband Mathew Hale and their 11-year old son, Rufus. Self-possessed and articulate, the boy was keenly interested in Hockney’s project and agreed to sit. His precocious seriousness was fascinating to Hockney in a world of diminishing attention spans. Inspired by this chance meeting, Hockney displays a painterly elan to match that of the old masters, capturing ambition and seriousness as well as vulnerability and youth. Staring at Rufus for many hours, Hockney recalls, his mind turned to his own self-portrait, seated in his house in Bradford in 1954. Thus an artist of almost 80 forged a largely silent bond with a boy not yet in his teens. 82 Portraits turns out to be a meditation on age, and the most commanding canvas in the series is that of its youngest sitter.

Rufus Hale, 23-25 Nov 2015.

Rufus Hale, 23-25 Nov 2015.

Creating these works has brought him a rare sense of artistic and personal fulfilment. “After periods of doing other things, I always come back to the portrait, and have a burst of sanity,” he says. The exhibition stands at the apex of his career, and it seems appropriate that it should be shown at the RA, founded nearly 250 years ago by Joshua Reynolds, a master of the portrait. Yet the work is not concluded. After painting, by now, almost 90 portraits in precisely the same format, Hockney’s enthusiasm is undiminished: “It’s endless. I’m seeing them clearer and clearer. I could go on for the rest of my days.”

• David Hockney: 82 Portraits and 1 Still-life will be published by the Royal Academy of Arts on 2 July (£30). The exhibition is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London W1J, 2 July-2 October.

A few sitters, such as philanthropist and collector Jacob Rothschild, whose schedules did not allow them to stay for the full period, were portrayed more quickly. Hockney is not averse to having a little fun with his sitters: Rothschild, lanky and quizzical, looks too tall for the chair; Barry Humphries sports a magnificently louche tie and pink trousers, a burlesque facade that masks his other identity as an astute patron and critic of art. More simple and heartfelt are the representations of Hockney’s family – his sister, Margaret, still in Bridlington, and brother John, who emigrated to Australia. A poignant absence is that of his mother and father, scrutinised so closely in earlier years.

Throughout the exhibition a benign atmosphere prevails, as if the tragedy of Elliott’s death can be assuaged only by a celebration of life. Perhaps the most significant encounter for Hockney came with a visit to LA by the artist Tacita Dean, her husband Mathew Hale and their 11-year old son, Rufus. Self-possessed and articulate, the boy was keenly interested in Hockney’s project and agreed to sit. His precocious seriousness was fascinating to Hockney in a world of diminishing attention spans. Inspired by this chance meeting, Hockney displays a painterly elan to match that of the old masters, capturing ambition and seriousness as well as vulnerability and youth. Staring at Rufus for many hours, Hockney recalls, his mind turned to his own self-portrait, seated in his house in Bradford in 1954. Thus an artist of almost 80 forged a largely silent bond with a boy not yet in his teens. 82 Portraits turns out to be a meditation on age, and the most commanding canvas in the series is that of its youngest sitter.

Creating these works has brought him a rare sense of artistic and personal fulfilment. “After periods of doing other things, I always come back to the portrait, and have a burst of sanity,” he says. The exhibition stands at the apex of his career, and it seems appropriate that it should be shown at the RA, founded nearly 250 years ago by Joshua Reynolds, a master of the portrait. Yet the work is not concluded. After painting, by now, almost 90 portraits in precisely the same format, Hockney’s enthusiasm is undiminished: “It’s endless. I’m seeing them clearer and clearer. I could go on for the rest of my days.”

• David Hockney: 82 Portraits and 1 Still-life will be published by the Royal Academy of Arts on 2 July (£30). The exhibition is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London W1J, 2 July-2 October.

No comments:

Post a Comment