He liked his drink, but he also liked kids / W.C. Fields biography explores the comic who laughed through his pain

W. C. Fields: A Biography (Knopf; 593 Pages; $35)

By James Curtis

Reviewed by Tom Nolan

sfgate.com

16 March 2003

On his deathbed, W.C. Fields, 66, for decades a relentless consumer of alcohol, confided to old friends: "I've often wondered how far I could have gone had I laid off the booze."

The brilliant comic-actor still managed to travel an amazing distance, despite the drink, in a half-century career that began in a summer casino near Philadelphia in 1898 and ended in 1946 in Hollywood.

Starting as a "tramp-juggler" act, Fields worked his way up through burlesque and vaudeville to the top of the bill; toured Europe, South Africa and Australia at the turn of the century; became a star of the Ziegfeld Follies and a hit on the Broadway stage. His first movies were made in the silent-picture era, but talkies displayed his unique gifts to the fullest; and he became (in Buster Keaton's judgment) one of "the greatest of all film comics." Guest appearances on network radio increased his celebrity. If he hadn't died, Fields might have been a success on TV, which he was looking forward to. And 20 years after his passing, he became more popular than ever as an iconoclastic icon whose appeal spanned the 1960s generation gap.

Fields' remarkable career, and the melancholy private life that accompanied it, are chronicled superbly in James Curtis' vivid and engrossing "W.C. Fields. " There have been other books about Fields, of course, but none seem so richly detailed nor so scrupulously researched. Curtis (author of previous biographies about James Whale and Preston Sturges) had access to Fields' papers and autobiographical notes, and he takes pains to differentiate between actual facts and apocrypha. ("Some of the quips attributed to Fields are best regarded as urban legends," Curtis notes. "I could not, for example, find a credible source for his oft-quoted remark about water.")

In lieu of dubious factoids, Curtis delivers a wealth of fresh information. Fields' story, and the milieux in which it unfolded, come to life as never before, and the truth, out of the rough-and-tumble past, is often more colorful than myth.

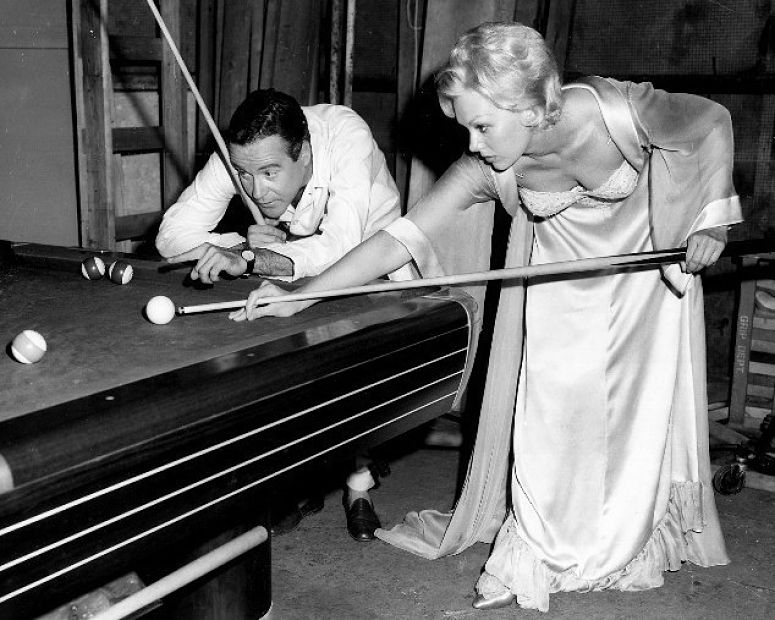

Here, for instance, is an incident from the Boston run of the Ziegfeld Follies of 1915, when Fields caught fellow performer Ed Wynn stealing laughs during a poolroom sketch: "Fields . . . found [Wynn] under the table making faces at the audience. Inverting his [pool] cue, Fields brought the butt end down on Wynn's skull with an earsplitting crack and continued the routine as his colleague lay out cold on the floor. Back in their dressing room, Fields, who was too much of a professional to hit Wynn in the face, seized him by the throat and beat his head against the wall. . . . [Later] Fields was in a genial, even conciliatory mood. 'Let's keep [the knockout] in,' he urged. 'It was the biggest laugh we got.' "

When Fields made the jump into movies, Curtis writes, he "had the courage to cast himself in the decidedly unfavorable light of a bully and a con man. He not only summed up the frustrations of the common man -- he did something about them." As a result, his best work has a timeless quality, and he was loved in a way quite different from his peers. Critic James Agee called Fields "the toughest and most warmly human of all screen comedians."

One secret of Fields' comedy was its pathos. "I never saw anything funny that wasn't terrible," he said. "If it causes pain, it's funny; if it doesn't, it isn't."

The pain in Fields' humor was present throughout his life, from his tough childhood in Philadelphia (not as Dickensian as he later sketched for journalists, but bad enough) to his death from cirrhosis of the liver.

Yet, through unpleasant family situations, various romantic entanglements, frequent professional frustrations and many physical ailments, he kept the pain at bay with his singular wit, and (for the most part) he avoided the behavioral excesses of his professional persona. Not at all the child hater many moviegoers assumed him to be, Fields was often gentle and generous to kids, one of whom -- Will Rogers' son Jim -- said: "He was like most all the comedians I have ever known -- men with very deep feelings and tremendous compassion."

Despite the warmth that was banked within, Fields could be cold, distant and suspicious. To Curtis' credit, he has shown Fields in all his aspects. The result is a fully dimensional portrait that does ample justice to its one-of-a- kind subject.

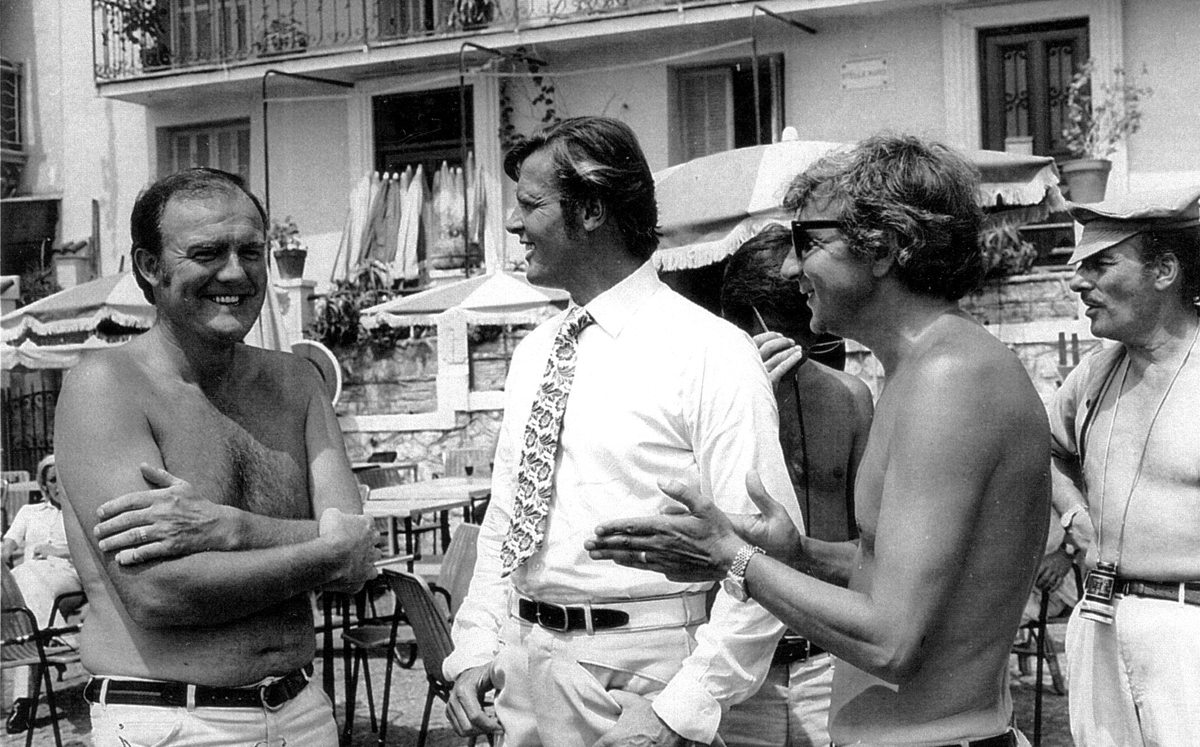

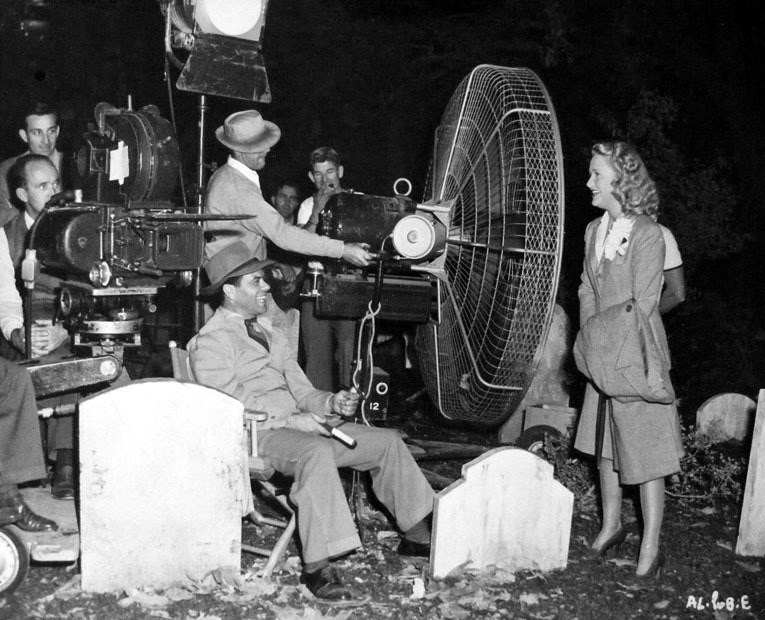

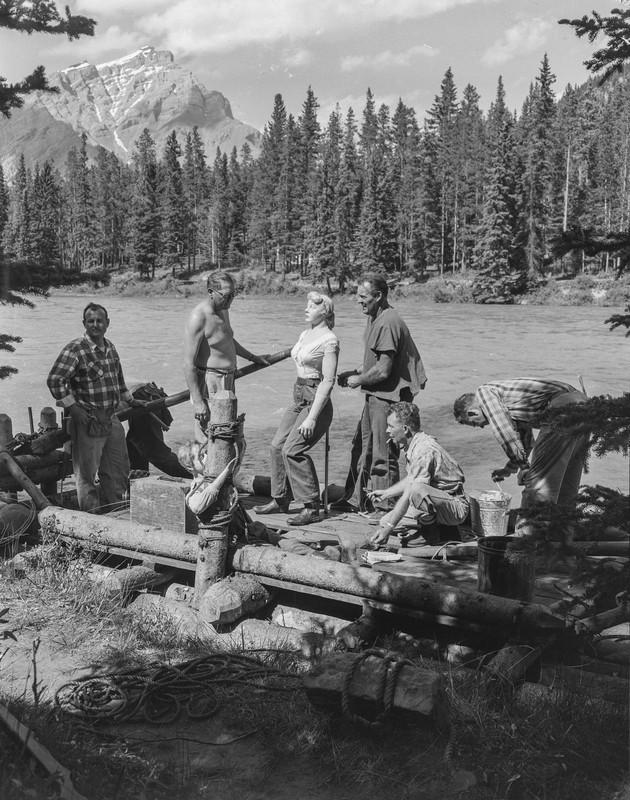

Terrifically illustrated with 100 photographs throughout its text, "W.C. Fields" is a joy to read, a masterful biography, perfectly paced and full of fine surprises. The only thing that could make it better would be a supplementary DVD of Fields' greatest scenes. Maybe one of the cable-TV movie channels will seize this good opportunity to schedule a monthlong W.C. Fields festival.

GloriaGraham_GlennFord.bmp)