Richard Brody

The New Yorker

1 October 2016

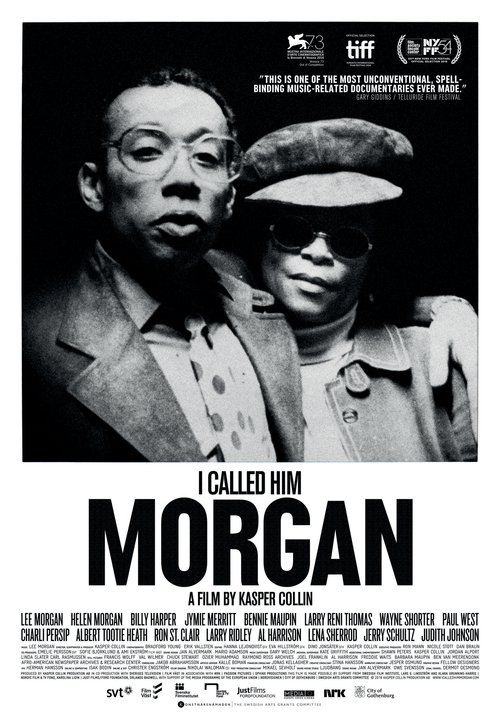

Some of the best offerings in this year’s New York Film Festival are documentaries. The festival opened last night with Ava DuVernay’s powerfully and passionately insightful documentary “13th,” a brilliant analysis of the historical roots of the politics behind today’s scourge of mass incarceration. Then, on Sunday and Monday, the festival will show the Swedish director Kasper Collin’s “I Called Him Morgan,” centered on the relationship between the great trumpeter Lee Morgan and his common-law wife, Helen Morgan, who shot him to death, in a Lower East Side jazz club, in 1972.

The backbone of Collin’s film is the sole audio interview with Helen Morgan, made in 1996, shortly before her death. The story that she tells combines with the story that Collin builds around it to provide a revelatory and moving portrait of a great musician and the other great people, whether celebrated (like musicians with whom Lee Morgan performed) or unheralded (like Helen), on whom his art and his life depended. It’s both a portrait of people and a historical landscape, a virtual vision of American times—the lives of black Americans in the age of Jim Crow and de-facto discrimination in the North—and of the artistry and personal style that arose in response to them.

Helen Morgan, born in 1926, had a hard youth in North Carolina and came to New York in the nineteen-forties, while still a teen-ager, to try to make her own way. She worked as a telephone operator, frequented jazz clubs, and became a sort of local celebrity, turning her home, in Hell’s Kitchen, into a virtual salon where artists and free spirits gathered. Meanwhile, Lee Morgan, born in 1938, was a brilliant young trumpet star, already a celebrated artist as a teen-ager. (He recorded his first album, leading his own band for the trailblazing Blue Note label, at the age of eighteen.) By 1960, he had recorded with John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, Tina Brooks, Sonny Clark, and Wayne Shorter, and was a member of Art Blakey’s group, one of the most popular and forward-looking (a rare combination) of the time. (Shorter joined that band, too—Blakey was one of the great talent scouts of the jazz world.)

In interviews with leading musicians of the era who knew and performed with Lee Morgan, such as Shorter, the drummers Albert (Tootie) Heath and Charli Persip, and the bassists Paul West and Jymie Merritt, Collin brings out stories of the fast life that went with the night life of jazz—fast cars, sexual adventures, fine clothing. Persip talks about racing his Austin-Healey against Morgan’s Triumph; Heath mentions speeding late at night through Central Park. Shorter speaks of performing in night clubs and drinking double or triple cognacs between sets: “I would drink and have like a thin veil around me—that’s my space, my little dream space—and we would play.”

There were also drugs, and Morgan became addicted to heroin. Quickly, Morgan had practical troubles as a result. Morgan became unreliable and left Blakey’s band; he also hurt himself seriously, nodding out beside a radiator and burning the side of his head, giving himself a bald spot and a scar as a result, which he concealed with a sort of comb-over for the rest of his life. Shorter, who was close with Morgan, felt that he was slipping away; in the film, looking at a photo of Morgan with his head bandaged, he talks to the photo—“What you doing, man? Lee, what you doing?” Morgan pawned his clothing to buy drugs; Heath recalls Morgan saying that he’d prefer to get high rather than play music. Morgan couldn’t get work—and then he met Helen Morgan at her apartment, and she made him her project. She helped him get off drugs, she helped him get his career back together, she took care of the practical aspects of his work—and he was playing more daringly than ever. Then he started to see another woman—Judith Johnson, who discusses their relationship in the film—and the ultimate result was the violent showdown in Slug’s, on East Third Street.

Collin’s film brings out these stories with a wealth of details energized by the experiences and the insights of his interview subjects as well as an engaging range of archival images and clips. Some performances by Lee Morgan are also highlighted on the soundtrack, but, of course, in a ninety-minute film, it’s inevitably the music itself that gets shortest shrift. That’s no knock on the film but, rather, a reason to do some listening apart from it.

Morgan’s style of hard bop, a style launched by Blakey, Miles Davis, Horace Silver, and others in the mid-nineteen-fifties, was a kind of simplification of bebop—an infusion of blues in the place of some of bop’s harmonic complexity. The result was a musical paradox—on the one hand, some of the music (such as Blakey’s and Silver’s) leaned toward popularity, without musical compromise. On the other, the simplifications opened a new and freer kind of musical space for soloists, pulling other hard-boppers (such as Davis and Jackie McLean) in the direction of the avant-garde and free jazz. Morgan’s own career moved in both directions—he played often with Blakey—and he also played frequently with McLean, as well as with Bobby Hutcherson, Andrew Hill, and other progressive luminaries of the nineteen-sixties.

http://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/a-documentary-about-the-life-and-tragic-death-of-the-great-jazz-trumpeter-lee-morgan

Some of the best offerings in this year’s New York Film Festival are documentaries. The festival opened last night with Ava DuVernay’s powerfully and passionately insightful documentary “13th,” a brilliant analysis of the historical roots of the politics behind today’s scourge of mass incarceration. Then, on Sunday and Monday, the festival will show the Swedish director Kasper Collin’s “I Called Him Morgan,” centered on the relationship between the great trumpeter Lee Morgan and his common-law wife, Helen Morgan, who shot him to death, in a Lower East Side jazz club, in 1972.

The backbone of Collin’s film is the sole audio interview with Helen Morgan, made in 1996, shortly before her death. The story that she tells combines with the story that Collin builds around it to provide a revelatory and moving portrait of a great musician and the other great people, whether celebrated (like musicians with whom Lee Morgan performed) or unheralded (like Helen), on whom his art and his life depended. It’s both a portrait of people and a historical landscape, a virtual vision of American times—the lives of black Americans in the age of Jim Crow and de-facto discrimination in the North—and of the artistry and personal style that arose in response to them.

Helen Morgan, born in 1926, had a hard youth in North Carolina and came to New York in the nineteen-forties, while still a teen-ager, to try to make her own way. She worked as a telephone operator, frequented jazz clubs, and became a sort of local celebrity, turning her home, in Hell’s Kitchen, into a virtual salon where artists and free spirits gathered. Meanwhile, Lee Morgan, born in 1938, was a brilliant young trumpet star, already a celebrated artist as a teen-ager. (He recorded his first album, leading his own band for the trailblazing Blue Note label, at the age of eighteen.) By 1960, he had recorded with John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, Tina Brooks, Sonny Clark, and Wayne Shorter, and was a member of Art Blakey’s group, one of the most popular and forward-looking (a rare combination) of the time. (Shorter joined that band, too—Blakey was one of the great talent scouts of the jazz world.)

In interviews with leading musicians of the era who knew and performed with Lee Morgan, such as Shorter, the drummers Albert (Tootie) Heath and Charli Persip, and the bassists Paul West and Jymie Merritt, Collin brings out stories of the fast life that went with the night life of jazz—fast cars, sexual adventures, fine clothing. Persip talks about racing his Austin-Healey against Morgan’s Triumph; Heath mentions speeding late at night through Central Park. Shorter speaks of performing in night clubs and drinking double or triple cognacs between sets: “I would drink and have like a thin veil around me—that’s my space, my little dream space—and we would play.”

There were also drugs, and Morgan became addicted to heroin. Quickly, Morgan had practical troubles as a result. Morgan became unreliable and left Blakey’s band; he also hurt himself seriously, nodding out beside a radiator and burning the side of his head, giving himself a bald spot and a scar as a result, which he concealed with a sort of comb-over for the rest of his life. Shorter, who was close with Morgan, felt that he was slipping away; in the film, looking at a photo of Morgan with his head bandaged, he talks to the photo—“What you doing, man? Lee, what you doing?” Morgan pawned his clothing to buy drugs; Heath recalls Morgan saying that he’d prefer to get high rather than play music. Morgan couldn’t get work—and then he met Helen Morgan at her apartment, and she made him her project. She helped him get off drugs, she helped him get his career back together, she took care of the practical aspects of his work—and he was playing more daringly than ever. Then he started to see another woman—Judith Johnson, who discusses their relationship in the film—and the ultimate result was the violent showdown in Slug’s, on East Third Street.

Collin’s film brings out these stories with a wealth of details energized by the experiences and the insights of his interview subjects as well as an engaging range of archival images and clips. Some performances by Lee Morgan are also highlighted on the soundtrack, but, of course, in a ninety-minute film, it’s inevitably the music itself that gets shortest shrift. That’s no knock on the film but, rather, a reason to do some listening apart from it.

Morgan’s style of hard bop, a style launched by Blakey, Miles Davis, Horace Silver, and others in the mid-nineteen-fifties, was a kind of simplification of bebop—an infusion of blues in the place of some of bop’s harmonic complexity. The result was a musical paradox—on the one hand, some of the music (such as Blakey’s and Silver’s) leaned toward popularity, without musical compromise. On the other, the simplifications opened a new and freer kind of musical space for soloists, pulling other hard-boppers (such as Davis and Jackie McLean) in the direction of the avant-garde and free jazz. Morgan’s own career moved in both directions—he played often with Blakey—and he also played frequently with McLean, as well as with Bobby Hutcherson, Andrew Hill, and other progressive luminaries of the nineteen-sixties.

http://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/a-documentary-about-the-life-and-tragic-death-of-the-great-jazz-trumpeter-lee-morgan

I Called Him Morgan review – jazz star's story comes in from the cold

Kasper Collin’s spellbinding documentary reveals the tender and tragic tale of hard bop trumpeter Lee Morgan and his common-law wife Helen

Jordan Hoffman

The Guardian

Monday 12 September 2016

With the best jazz recordings you recognise the beginning and know where it’s going to wind up, but it’s the road there that’s unpredictable. To that end, Kasper Collin’s I Called Him Morgan isn’t just the greatest jazz documentary since Let’s Get Lost, it’s a documentary-as-jazz. Spellbinding, mercurial, hallucinatory, exuberant, tragic … aw hell, man, those are a lot of heavy words, but have you heard Lee Morgan’s music? More importantly, do you know the story of his life?

Lee Morgan may have been one of the most important trumpet players in jazz, but he doesn’t have the household name status of Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie or Miles Davis. Unfortunately, like Bix Beiderbecke and Clifford Brown, he died way too young. While Morgan’s output as the leader of his own working group is outstanding (may I recommend to you The Sidewinder, The Gigolo or perhaps even The Rumproller) he was also a linchpin member of the classic Blue Note sound overseen by producers Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff and engineer Rudy Van Gelder.

That’s Lee beside John Coltrane on the legendary 1957 album Blue Train. And that’s Lee as part of the Jazz Messengers, the supergroup led by drummer Art Blakey that ostensibly invented the subgenre known as hard bop. For those who don’t know much about jazz, this sound is what you think about when you think about jazz. And it’s Lee Morgan blowing the horn. And it’s Lee Morgan’s squeak at the 0:59 mark of Moanin’ that gives this art form its ineffable quality.

But I Called Him Morgan is far from a traditional documentary. Its story-within-a-story begins with a 2013 interview with Larry Reni Thomas, a North Carolina teacher who just so happens to be a legendary jazz DJ. In the mid 1990s, as he was greeting new students in an adult education class, he realised his new pupil (nearing age 70) was Helen Morgan, Lee’s widow. In 1996 Thomas sat down with an inexpensive tape recorder and asked her questions. A month later she died.

Collin turns to that plain, unlabelled white tape, marred by squeaks and hisses, and from it emerges the ghost of a voice. Helen Morgan was born in the 1920s in rural North Carolina, had two children out of wedlock at ages 13 and 14, then left for New York at 17 after her new husband passed away in an accident. She got a job at an answering service, and her apartment, located near all the jazz hotspots on West 53rd street, became something of a haven for musicians – mostly because she took pride in her cooking and was ready to feed anyone who came to her door.

At the same time, Lee Morgan was the young wonder on the scene. Collin traces his time with the Jazz Messengers using a deluge of remarkable photographs set to music. Commentary from Wayne Shorter, Tootie Heath, Larry Ridley and others offer insight, but not much can top the swirl of images. In 1964, Morgan recorded Search for the New Land (a precursor of sorts, I would argue, to the spiritual jazz of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme or Pharoah Sanders’s Karma) but, by that time, he had a debilitating drug addiction.

Lee and Helen finally collided in 1967. He was strung out and freezing on the street, and she brought him in from the cold. In Thomas’s audiotape, her recollection is so tender and so sad. “Why don’t you have a coat?” she repeats, in a thin, quaking voice.

Though 13 years his senior, she became his lover after being his nurse. Once he was cleaned up, they moved to the Bronx and he restarted his career, with her as his manager. But their relationship was not traditional. They were never formally married and Helen’s son, who was now back in the picture, was the same age as Lee. Though clean, one gets the impression Lee Morgan was still in a fog, and when he began a relationship with a new woman living in New Jersey, trouble began to mount.

I’m lucky to have spent many of my younger years as a jazz enthusiast in New York City and I swear to you it isn’t revisionist history that the music sounds better on snowy nights. Winter images (recreated on what appears to be 8mm) recur in I Called Him Morgan – snow outside the car window while passing the bridges surrounding Manhattan – and the film’s climax is inexorably linked to a horrible blizzard.

Though Lee and Helen Morgan’s fate is easily learned with a quick Google search, I’d rather leave it unspoken, out there in memory’s snowdrift, something strange and indescribable, like this sad but still beautiful film itself.

Monday 12 September 2016

With the best jazz recordings you recognise the beginning and know where it’s going to wind up, but it’s the road there that’s unpredictable. To that end, Kasper Collin’s I Called Him Morgan isn’t just the greatest jazz documentary since Let’s Get Lost, it’s a documentary-as-jazz. Spellbinding, mercurial, hallucinatory, exuberant, tragic … aw hell, man, those are a lot of heavy words, but have you heard Lee Morgan’s music? More importantly, do you know the story of his life?

Lee Morgan may have been one of the most important trumpet players in jazz, but he doesn’t have the household name status of Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie or Miles Davis. Unfortunately, like Bix Beiderbecke and Clifford Brown, he died way too young. While Morgan’s output as the leader of his own working group is outstanding (may I recommend to you The Sidewinder, The Gigolo or perhaps even The Rumproller) he was also a linchpin member of the classic Blue Note sound overseen by producers Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff and engineer Rudy Van Gelder.

That’s Lee beside John Coltrane on the legendary 1957 album Blue Train. And that’s Lee as part of the Jazz Messengers, the supergroup led by drummer Art Blakey that ostensibly invented the subgenre known as hard bop. For those who don’t know much about jazz, this sound is what you think about when you think about jazz. And it’s Lee Morgan blowing the horn. And it’s Lee Morgan’s squeak at the 0:59 mark of Moanin’ that gives this art form its ineffable quality.

But I Called Him Morgan is far from a traditional documentary. Its story-within-a-story begins with a 2013 interview with Larry Reni Thomas, a North Carolina teacher who just so happens to be a legendary jazz DJ. In the mid 1990s, as he was greeting new students in an adult education class, he realised his new pupil (nearing age 70) was Helen Morgan, Lee’s widow. In 1996 Thomas sat down with an inexpensive tape recorder and asked her questions. A month later she died.

Collin turns to that plain, unlabelled white tape, marred by squeaks and hisses, and from it emerges the ghost of a voice. Helen Morgan was born in the 1920s in rural North Carolina, had two children out of wedlock at ages 13 and 14, then left for New York at 17 after her new husband passed away in an accident. She got a job at an answering service, and her apartment, located near all the jazz hotspots on West 53rd street, became something of a haven for musicians – mostly because she took pride in her cooking and was ready to feed anyone who came to her door.

At the same time, Lee Morgan was the young wonder on the scene. Collin traces his time with the Jazz Messengers using a deluge of remarkable photographs set to music. Commentary from Wayne Shorter, Tootie Heath, Larry Ridley and others offer insight, but not much can top the swirl of images. In 1964, Morgan recorded Search for the New Land (a precursor of sorts, I would argue, to the spiritual jazz of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme or Pharoah Sanders’s Karma) but, by that time, he had a debilitating drug addiction.

Lee and Helen finally collided in 1967. He was strung out and freezing on the street, and she brought him in from the cold. In Thomas’s audiotape, her recollection is so tender and so sad. “Why don’t you have a coat?” she repeats, in a thin, quaking voice.

Though 13 years his senior, she became his lover after being his nurse. Once he was cleaned up, they moved to the Bronx and he restarted his career, with her as his manager. But their relationship was not traditional. They were never formally married and Helen’s son, who was now back in the picture, was the same age as Lee. Though clean, one gets the impression Lee Morgan was still in a fog, and when he began a relationship with a new woman living in New Jersey, trouble began to mount.

I’m lucky to have spent many of my younger years as a jazz enthusiast in New York City and I swear to you it isn’t revisionist history that the music sounds better on snowy nights. Winter images (recreated on what appears to be 8mm) recur in I Called Him Morgan – snow outside the car window while passing the bridges surrounding Manhattan – and the film’s climax is inexorably linked to a horrible blizzard.

Though Lee and Helen Morgan’s fate is easily learned with a quick Google search, I’d rather leave it unspoken, out there in memory’s snowdrift, something strange and indescribable, like this sad but still beautiful film itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment