And in answer to your question: young Gene Kelly, third from left.

Sunday, 30 April 2017

Saturday, 29 April 2017

Dead Poets Society #36 Walt Whitman: When I heard the Learn’d Astronomer

WHEN I heard the learn’d astronomer;

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me;

When I was shown the charts and the diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them;

When I, sitting, heard the astronomer, where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room,

How soon, unaccountable, I became tired and sick;

Till rising and gliding out, I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

Unfortunately, compressing the lines to fit in the blog post ruins the effect of the build-up to the longest line...

Friday, 28 April 2017

Jonathan Demme RIP

Jonathan Demme obituary

US film director whose 1991 thriller The Silence of the Lambs won five OscarsRyan Gilbey

The Guardian

Wednesday 26 April 2017

Jonathan Demme, who has died aged 73 from complications from cancer, rose from his colourful if tawdry beginnings under the aegis of the exploitation maestro Roger Corman to become one of the most eclectic, delightful and original film-makers in Hollywood. He also happened to be one of the nicest: the compassionate sensibility that lent his work its warmth and musicality was no put-on. Plainly put, he loved people.

Even his darkest work, such as the hit thriller The Silence of the Lambs (1991), which gave him his first taste of box-office success nearly two decades into his career and also brought him a best director Oscar, had a beguiling tenderness about it. For all that film’s gruesome frights, it was the connection between the FBI agent Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) and her macabre mentor, the serial killer Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins), that lent the film its emotional bite.

His movies could be bewilderingly diverse – he made the innovative concert film Stop Making Sense (1984), the uproarious screwball thriller Something Wild (1986), the Aids drama Philadelphia (1993) and a remake of The Manchurian Candidate (2004) – but they were united by their colour and vim, as well as a deep-seated sense of conscientiousness and community. Demme cared deeply about what he put on the screen.

“That’s one of the joyful aspects of the work and I also feel it’s part of my responsibility as a film-maker,” he said in 2004. “You have to remember that the behaviour you visualise on screen will be witnessed by thousands or millions of people, and will ultimately say something about us as a species. That’s why it gets harder for me to have pure villains in my films. When people tell me, ‘Oh, Meryl Streep’s great in The Manchurian Candidate, I hated her so much!’ – well, I don’t wanna hear the ‘hated’ part, because I see her as a fully fledged, emotional person.”

Crucially, he never lost touch with his B-movie roots. He always remembered Corman’s advice to keep the viewer’s eye stimulated; as a mark of affection, he gave Corman cameo roles in most of his films.

He was born in Baldwin, Long Island, the son of Robert Demme, who worked in PR, and his wife, Dorothy (nee Rogers). Jonathan was educated at the University of Florida, where he became a film critic on the college newspaper and came to the attention of the producer Joseph E Levine, who was so impressed (not least by Demme’s positive review of Zulu, which Levine had produced) that he hired him as a publicity writer.

Demme met Corman while working in London on publicity for the latter’s war film Von Richthofen and Brown (1971), and was soon recruited into the stable of writer-directors that had already spawned Francis Ford Coppola and Peter Bogdanovich. He shot one scene of the sex film Secrets of a Door-to-Door Salesman (aka Naughty Wives) (1973) and wrote assorted scripts for Corman, such as Angels Hard As They Come (1971) and The Hot Box (1972), before making his directing debut with the women-in-prison thriller Caged Heat (1974) and the lighthearted gangster movie Crazy Mama (1975). In both instances, he insisted that the criminals should survive; Crazy Mama even ends with the outlaws cheerfully running a hot-dog stand. “They escaped! You’ve got no ending!” cried an outraged Corman.

After his last outright exploitation picture, the revenge thriller Fighting Mad (1976), Demme made his major studio debut with Citizens Band, aka Handle With Care (1977), intended by Paramount to cash in on the CB radio boom but shaped by Demme into a sweet-natured comic roundelay. The agent turned producer Freddie Fields interfered in the production and even sacked Demme at one point, until Roman Polanski, who had heard about the incident through a mutual friend, demanded his reinstatement. Glowing reviews (Pauline Kael likened Demme to Renoir) did not translate into ticket sales and the film was a flop, as was Last Embrace (1979), his witty homage to Vertigo. There was praise, too, for Melvin and Howard (1980), which dramatised the true story of an unassuming milkman who helps an old man stranded in the desert one night after a motorcycle accident; only later does he discover that he came to the rescue of Howard Hughes and that he has been made a beneficiary in his will. Demme’s intimate, easygoing humour, and his affectionate work with his cast (including Mary Steenburgen, who won an Oscar) brought purpose and definition to this featherweight tale.

He had another bruising encounter with Hollywood on Swing Shift (1984), a wartime comedy-drama which was re-edited by its star Goldie Hawn, who was also the producer. But Stop Making Sense was a triumph – a fully cinematic visual record of a Talking Heads performance, with the band and the show assembling gradually, song by song, beginning with just the singer David Byrne on stage with a guitar and a tape-recorder and ending with a full battalion of musicians, dancers, backing singers, props and costumes (including, famously, Byrne’s boxy, over-sized suit).

Something Wild threw together an uptight businessman (Jeff Daniels) and an unpredictable kook (Melanie Griffith) in an on-the-lam adventure steeped in colour, eccentricity and music; Demme negotiated masterfully the switch halfway through from comedy to suspense.

In Swimming to Cambodia (1987), he brought to a one-man show by the actor and raconteur Spalding Gray some of the same minimalist magic of Stop Making Sense and delivered another quirky marriage of crime and comedy in Married to the Mob (1988), starring Michelle Pfeiffer as a mafia widow. However, the audiences were not won over. “I wondered if I was missing some commercial gene,” he said. “Or if I had a curse.”

Demme claimed to be as surprised as anyone about the success of The Silence of the Lambs. “I had just done what I always did. Only this time it worked.” That was an understatement. The film was only the third in history to win all five major Oscars; it made more than $240m worldwide and its influence was strongly felt on the thriller genre, though it was to Demme’s credit that he opted not to direct the sensationalist sequel (Hannibal) and prequel (Red Dragon). Philadelphia, about the efforts of a lawyer (Tom Hanks) to sue the practice which dismissed him after discovering that he was dying from Aids, could hardly have been more different. It was credited with encouraging a better understanding of HIV/Aids.

“We got together and tried to come up with a movie that would help push for a cure and save lives,” Demme said. “We didn’t want to make a film that would appeal to an audience of people like us, who already had a predisposition for caring about people with Aids. We wanted to reach the people who couldn’t care less about people with Aids. That was our target audience.”

He later conceded that the success of those two films changed the course of his career, and not exclusively for the good. “There is some seductive upward spiral, which I might have got sucked into, where once you have success, you get to make even more expensive films, you get paid more and your work seems even more ‘important’ and ‘major.’” His adaptation of Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved (1998), though intensely powerful and boasting a spectacular performance byThandie Newton, did not continue his box-office success, while The Truth About Charlie (2002) was an insipid remake of the much-loved caper Charade.

He rediscovered his earlier vitality with Rachel Getting Married (2008), a fizzy family drama which drew on memories of his mother’s alcoholism and starred Anne Hathaway as a woman leaving rehab to attend her sister’s wedding. Shot with hand-held cameras (camcorders were even placed in the hands of the extras playing wedding guests, and their footage spliced into the movie) and peppered with impromptu musical turns, it fulfilled Demme’s ambition to create “the most beautiful home movie ever made.” Less well-received, but brimming with bonhomie, was Ricki and the Flash (2015), with Meryl Streep as a rock singer re-connecting with the daughter she abandoned.

Aside from his fiction work, Demme was an accomplished documentary maker whose subjects ranged from family (his cousin, an Episcopalian minister, in the 1992 Cousin Bobby) to musicians (Robyn Hitchcock, Neil Young, Justin Timberlake) and politicians (Jimmy Carter in the 2007 Man from Plains).

In 2008, I asked him whether he had anything to add to the formula he had outlined in 1986 for making a decent movie – “You get a good script, good actors and try not to screw it up.” He let out a joyful laugh and gave an exaggerated slap of the thigh: “That’s the formula, baby.”

He is survived by his second wife, Joanne Howard, and three children, Ramona, Brooklyn and Jos.

• Robert Jonathan Demme, film director, born 22 February 1944; died 26 April 2017

Wednesday 26 April 2017

Jonathan Demme, who has died aged 73 from complications from cancer, rose from his colourful if tawdry beginnings under the aegis of the exploitation maestro Roger Corman to become one of the most eclectic, delightful and original film-makers in Hollywood. He also happened to be one of the nicest: the compassionate sensibility that lent his work its warmth and musicality was no put-on. Plainly put, he loved people.

Even his darkest work, such as the hit thriller The Silence of the Lambs (1991), which gave him his first taste of box-office success nearly two decades into his career and also brought him a best director Oscar, had a beguiling tenderness about it. For all that film’s gruesome frights, it was the connection between the FBI agent Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) and her macabre mentor, the serial killer Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins), that lent the film its emotional bite.

His movies could be bewilderingly diverse – he made the innovative concert film Stop Making Sense (1984), the uproarious screwball thriller Something Wild (1986), the Aids drama Philadelphia (1993) and a remake of The Manchurian Candidate (2004) – but they were united by their colour and vim, as well as a deep-seated sense of conscientiousness and community. Demme cared deeply about what he put on the screen.

“That’s one of the joyful aspects of the work and I also feel it’s part of my responsibility as a film-maker,” he said in 2004. “You have to remember that the behaviour you visualise on screen will be witnessed by thousands or millions of people, and will ultimately say something about us as a species. That’s why it gets harder for me to have pure villains in my films. When people tell me, ‘Oh, Meryl Streep’s great in The Manchurian Candidate, I hated her so much!’ – well, I don’t wanna hear the ‘hated’ part, because I see her as a fully fledged, emotional person.”

Crucially, he never lost touch with his B-movie roots. He always remembered Corman’s advice to keep the viewer’s eye stimulated; as a mark of affection, he gave Corman cameo roles in most of his films.

He was born in Baldwin, Long Island, the son of Robert Demme, who worked in PR, and his wife, Dorothy (nee Rogers). Jonathan was educated at the University of Florida, where he became a film critic on the college newspaper and came to the attention of the producer Joseph E Levine, who was so impressed (not least by Demme’s positive review of Zulu, which Levine had produced) that he hired him as a publicity writer.

Demme met Corman while working in London on publicity for the latter’s war film Von Richthofen and Brown (1971), and was soon recruited into the stable of writer-directors that had already spawned Francis Ford Coppola and Peter Bogdanovich. He shot one scene of the sex film Secrets of a Door-to-Door Salesman (aka Naughty Wives) (1973) and wrote assorted scripts for Corman, such as Angels Hard As They Come (1971) and The Hot Box (1972), before making his directing debut with the women-in-prison thriller Caged Heat (1974) and the lighthearted gangster movie Crazy Mama (1975). In both instances, he insisted that the criminals should survive; Crazy Mama even ends with the outlaws cheerfully running a hot-dog stand. “They escaped! You’ve got no ending!” cried an outraged Corman.

After his last outright exploitation picture, the revenge thriller Fighting Mad (1976), Demme made his major studio debut with Citizens Band, aka Handle With Care (1977), intended by Paramount to cash in on the CB radio boom but shaped by Demme into a sweet-natured comic roundelay. The agent turned producer Freddie Fields interfered in the production and even sacked Demme at one point, until Roman Polanski, who had heard about the incident through a mutual friend, demanded his reinstatement. Glowing reviews (Pauline Kael likened Demme to Renoir) did not translate into ticket sales and the film was a flop, as was Last Embrace (1979), his witty homage to Vertigo. There was praise, too, for Melvin and Howard (1980), which dramatised the true story of an unassuming milkman who helps an old man stranded in the desert one night after a motorcycle accident; only later does he discover that he came to the rescue of Howard Hughes and that he has been made a beneficiary in his will. Demme’s intimate, easygoing humour, and his affectionate work with his cast (including Mary Steenburgen, who won an Oscar) brought purpose and definition to this featherweight tale.

He had another bruising encounter with Hollywood on Swing Shift (1984), a wartime comedy-drama which was re-edited by its star Goldie Hawn, who was also the producer. But Stop Making Sense was a triumph – a fully cinematic visual record of a Talking Heads performance, with the band and the show assembling gradually, song by song, beginning with just the singer David Byrne on stage with a guitar and a tape-recorder and ending with a full battalion of musicians, dancers, backing singers, props and costumes (including, famously, Byrne’s boxy, over-sized suit).

Something Wild threw together an uptight businessman (Jeff Daniels) and an unpredictable kook (Melanie Griffith) in an on-the-lam adventure steeped in colour, eccentricity and music; Demme negotiated masterfully the switch halfway through from comedy to suspense.

In Swimming to Cambodia (1987), he brought to a one-man show by the actor and raconteur Spalding Gray some of the same minimalist magic of Stop Making Sense and delivered another quirky marriage of crime and comedy in Married to the Mob (1988), starring Michelle Pfeiffer as a mafia widow. However, the audiences were not won over. “I wondered if I was missing some commercial gene,” he said. “Or if I had a curse.”

Demme claimed to be as surprised as anyone about the success of The Silence of the Lambs. “I had just done what I always did. Only this time it worked.” That was an understatement. The film was only the third in history to win all five major Oscars; it made more than $240m worldwide and its influence was strongly felt on the thriller genre, though it was to Demme’s credit that he opted not to direct the sensationalist sequel (Hannibal) and prequel (Red Dragon). Philadelphia, about the efforts of a lawyer (Tom Hanks) to sue the practice which dismissed him after discovering that he was dying from Aids, could hardly have been more different. It was credited with encouraging a better understanding of HIV/Aids.

“We got together and tried to come up with a movie that would help push for a cure and save lives,” Demme said. “We didn’t want to make a film that would appeal to an audience of people like us, who already had a predisposition for caring about people with Aids. We wanted to reach the people who couldn’t care less about people with Aids. That was our target audience.”

He later conceded that the success of those two films changed the course of his career, and not exclusively for the good. “There is some seductive upward spiral, which I might have got sucked into, where once you have success, you get to make even more expensive films, you get paid more and your work seems even more ‘important’ and ‘major.’” His adaptation of Toni Morrison’s novel Beloved (1998), though intensely powerful and boasting a spectacular performance byThandie Newton, did not continue his box-office success, while The Truth About Charlie (2002) was an insipid remake of the much-loved caper Charade.

He rediscovered his earlier vitality with Rachel Getting Married (2008), a fizzy family drama which drew on memories of his mother’s alcoholism and starred Anne Hathaway as a woman leaving rehab to attend her sister’s wedding. Shot with hand-held cameras (camcorders were even placed in the hands of the extras playing wedding guests, and their footage spliced into the movie) and peppered with impromptu musical turns, it fulfilled Demme’s ambition to create “the most beautiful home movie ever made.” Less well-received, but brimming with bonhomie, was Ricki and the Flash (2015), with Meryl Streep as a rock singer re-connecting with the daughter she abandoned.

Aside from his fiction work, Demme was an accomplished documentary maker whose subjects ranged from family (his cousin, an Episcopalian minister, in the 1992 Cousin Bobby) to musicians (Robyn Hitchcock, Neil Young, Justin Timberlake) and politicians (Jimmy Carter in the 2007 Man from Plains).

In 2008, I asked him whether he had anything to add to the formula he had outlined in 1986 for making a decent movie – “You get a good script, good actors and try not to screw it up.” He let out a joyful laugh and gave an exaggerated slap of the thigh: “That’s the formula, baby.”

He is survived by his second wife, Joanne Howard, and three children, Ramona, Brooklyn and Jos.

• Robert Jonathan Demme, film director, born 22 February 1944; died 26 April 2017

Thursday, 27 April 2017

Last night's set lists

At The Habit, York: -

Ron Elderly: -

One More Cup Of Coffee

The River

Need Your Love So Bad

Da Elderly: -

Love Song

I'm Just A Loser

In The Morning Light

The Elderly Brothers: -

Yes I Will

No Reply

You Got It

I Saw Her Standing There

As expected after last week's bumper attendance, it was a rather quiet night, for both players and punters. So it was 3 songs each in the end. Worth a mention was a lovely rendition of Sandy Denny's Who Knows Where The Time Goes by regular Deb Simpson. The Elderly Brothers closed the show with songs by The Hollies, The Beatles and Roy Orbison. A random unplugged session followed until closing time - another enjoyable evening at The Habit.

Ron Elderly: -

One More Cup Of Coffee

The River

Need Your Love So Bad

Da Elderly: -

Love Song

I'm Just A Loser

In The Morning Light

The Elderly Brothers: -

Yes I Will

No Reply

You Got It

I Saw Her Standing There

As expected after last week's bumper attendance, it was a rather quiet night, for both players and punters. So it was 3 songs each in the end. Worth a mention was a lovely rendition of Sandy Denny's Who Knows Where The Time Goes by regular Deb Simpson. The Elderly Brothers closed the show with songs by The Hollies, The Beatles and Roy Orbison. A random unplugged session followed until closing time - another enjoyable evening at The Habit.

Wednesday, 26 April 2017

Tuesday, 25 April 2017

Relief!

Of course, it remains to be seen whether Rafa will stay and how much money Trashley is prepared to part with... A conservative estimate would suggest at least five (good) players will be needed to reach even mid-table. Fingers crossed. As usual.

Monday, 24 April 2017

Sunday, 23 April 2017

Friday, 21 April 2017

Dead Poets Society #35 Randall Jarrell: The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner

The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner by Randall Jarrell

From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State,

From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze.

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.

Thursday, 20 April 2017

Last night's set lists

At The Habit, York: -

Ron Elderly: -

Always On My Mind

Suspicious Minds

Da Elderly: -

Laurel Canyon Home

Helpless

The Elderly Brothers: -

Then I Kissed Her

Sitting In The Park

When Will I Be Loved

I Saw Her Standing There

Love Hurts

What a contrast to last week! The place was packed from the off and one or two prospective players came too late to get a turn. The solitary barmaid worked her socks off! As usual there was a wide range of music to be heard including a duo performing Norah Jones' Don't Know Why - a beautifully wistful vocal delivery too. The Elderly Brothers closed the show and included a 'new' song, Georgie Fame's version of Sitting In The Park. The after-show entertainment continued unplugged until closing time - The Elderlys being peppered with requests for sixties classics; we obliged with songs from The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, Chuck Berry etc. The most unexpected request was from a lass asking for Neil Young's Human Highway - a first for that particular song.

Ron Elderly: -

Always On My Mind

Suspicious Minds

Da Elderly: -

Laurel Canyon Home

Helpless

The Elderly Brothers: -

Then I Kissed Her

Sitting In The Park

When Will I Be Loved

I Saw Her Standing There

Love Hurts

What a contrast to last week! The place was packed from the off and one or two prospective players came too late to get a turn. The solitary barmaid worked her socks off! As usual there was a wide range of music to be heard including a duo performing Norah Jones' Don't Know Why - a beautifully wistful vocal delivery too. The Elderly Brothers closed the show and included a 'new' song, Georgie Fame's version of Sitting In The Park. The after-show entertainment continued unplugged until closing time - The Elderlys being peppered with requests for sixties classics; we obliged with songs from The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, Chuck Berry etc. The most unexpected request was from a lass asking for Neil Young's Human Highway - a first for that particular song.

Wednesday, 19 April 2017

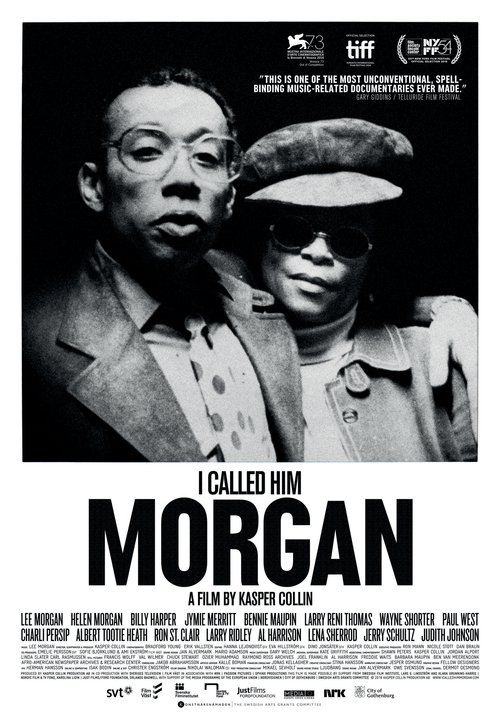

I Called Him Morgan - documentary about Jazz trumpeter Lee Morgan - reviews

Richard Brody

The New Yorker

1 October 2016

Some of the best offerings in this year’s New York Film Festival are documentaries. The festival opened last night with Ava DuVernay’s powerfully and passionately insightful documentary “13th,” a brilliant analysis of the historical roots of the politics behind today’s scourge of mass incarceration. Then, on Sunday and Monday, the festival will show the Swedish director Kasper Collin’s “I Called Him Morgan,” centered on the relationship between the great trumpeter Lee Morgan and his common-law wife, Helen Morgan, who shot him to death, in a Lower East Side jazz club, in 1972.

The backbone of Collin’s film is the sole audio interview with Helen Morgan, made in 1996, shortly before her death. The story that she tells combines with the story that Collin builds around it to provide a revelatory and moving portrait of a great musician and the other great people, whether celebrated (like musicians with whom Lee Morgan performed) or unheralded (like Helen), on whom his art and his life depended. It’s both a portrait of people and a historical landscape, a virtual vision of American times—the lives of black Americans in the age of Jim Crow and de-facto discrimination in the North—and of the artistry and personal style that arose in response to them.

Helen Morgan, born in 1926, had a hard youth in North Carolina and came to New York in the nineteen-forties, while still a teen-ager, to try to make her own way. She worked as a telephone operator, frequented jazz clubs, and became a sort of local celebrity, turning her home, in Hell’s Kitchen, into a virtual salon where artists and free spirits gathered. Meanwhile, Lee Morgan, born in 1938, was a brilliant young trumpet star, already a celebrated artist as a teen-ager. (He recorded his first album, leading his own band for the trailblazing Blue Note label, at the age of eighteen.) By 1960, he had recorded with John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, Tina Brooks, Sonny Clark, and Wayne Shorter, and was a member of Art Blakey’s group, one of the most popular and forward-looking (a rare combination) of the time. (Shorter joined that band, too—Blakey was one of the great talent scouts of the jazz world.)

In interviews with leading musicians of the era who knew and performed with Lee Morgan, such as Shorter, the drummers Albert (Tootie) Heath and Charli Persip, and the bassists Paul West and Jymie Merritt, Collin brings out stories of the fast life that went with the night life of jazz—fast cars, sexual adventures, fine clothing. Persip talks about racing his Austin-Healey against Morgan’s Triumph; Heath mentions speeding late at night through Central Park. Shorter speaks of performing in night clubs and drinking double or triple cognacs between sets: “I would drink and have like a thin veil around me—that’s my space, my little dream space—and we would play.”

There were also drugs, and Morgan became addicted to heroin. Quickly, Morgan had practical troubles as a result. Morgan became unreliable and left Blakey’s band; he also hurt himself seriously, nodding out beside a radiator and burning the side of his head, giving himself a bald spot and a scar as a result, which he concealed with a sort of comb-over for the rest of his life. Shorter, who was close with Morgan, felt that he was slipping away; in the film, looking at a photo of Morgan with his head bandaged, he talks to the photo—“What you doing, man? Lee, what you doing?” Morgan pawned his clothing to buy drugs; Heath recalls Morgan saying that he’d prefer to get high rather than play music. Morgan couldn’t get work—and then he met Helen Morgan at her apartment, and she made him her project. She helped him get off drugs, she helped him get his career back together, she took care of the practical aspects of his work—and he was playing more daringly than ever. Then he started to see another woman—Judith Johnson, who discusses their relationship in the film—and the ultimate result was the violent showdown in Slug’s, on East Third Street.

Collin’s film brings out these stories with a wealth of details energized by the experiences and the insights of his interview subjects as well as an engaging range of archival images and clips. Some performances by Lee Morgan are also highlighted on the soundtrack, but, of course, in a ninety-minute film, it’s inevitably the music itself that gets shortest shrift. That’s no knock on the film but, rather, a reason to do some listening apart from it.

Morgan’s style of hard bop, a style launched by Blakey, Miles Davis, Horace Silver, and others in the mid-nineteen-fifties, was a kind of simplification of bebop—an infusion of blues in the place of some of bop’s harmonic complexity. The result was a musical paradox—on the one hand, some of the music (such as Blakey’s and Silver’s) leaned toward popularity, without musical compromise. On the other, the simplifications opened a new and freer kind of musical space for soloists, pulling other hard-boppers (such as Davis and Jackie McLean) in the direction of the avant-garde and free jazz. Morgan’s own career moved in both directions—he played often with Blakey—and he also played frequently with McLean, as well as with Bobby Hutcherson, Andrew Hill, and other progressive luminaries of the nineteen-sixties.

http://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/a-documentary-about-the-life-and-tragic-death-of-the-great-jazz-trumpeter-lee-morgan

Some of the best offerings in this year’s New York Film Festival are documentaries. The festival opened last night with Ava DuVernay’s powerfully and passionately insightful documentary “13th,” a brilliant analysis of the historical roots of the politics behind today’s scourge of mass incarceration. Then, on Sunday and Monday, the festival will show the Swedish director Kasper Collin’s “I Called Him Morgan,” centered on the relationship between the great trumpeter Lee Morgan and his common-law wife, Helen Morgan, who shot him to death, in a Lower East Side jazz club, in 1972.

The backbone of Collin’s film is the sole audio interview with Helen Morgan, made in 1996, shortly before her death. The story that she tells combines with the story that Collin builds around it to provide a revelatory and moving portrait of a great musician and the other great people, whether celebrated (like musicians with whom Lee Morgan performed) or unheralded (like Helen), on whom his art and his life depended. It’s both a portrait of people and a historical landscape, a virtual vision of American times—the lives of black Americans in the age of Jim Crow and de-facto discrimination in the North—and of the artistry and personal style that arose in response to them.

Helen Morgan, born in 1926, had a hard youth in North Carolina and came to New York in the nineteen-forties, while still a teen-ager, to try to make her own way. She worked as a telephone operator, frequented jazz clubs, and became a sort of local celebrity, turning her home, in Hell’s Kitchen, into a virtual salon where artists and free spirits gathered. Meanwhile, Lee Morgan, born in 1938, was a brilliant young trumpet star, already a celebrated artist as a teen-ager. (He recorded his first album, leading his own band for the trailblazing Blue Note label, at the age of eighteen.) By 1960, he had recorded with John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, Tina Brooks, Sonny Clark, and Wayne Shorter, and was a member of Art Blakey’s group, one of the most popular and forward-looking (a rare combination) of the time. (Shorter joined that band, too—Blakey was one of the great talent scouts of the jazz world.)

In interviews with leading musicians of the era who knew and performed with Lee Morgan, such as Shorter, the drummers Albert (Tootie) Heath and Charli Persip, and the bassists Paul West and Jymie Merritt, Collin brings out stories of the fast life that went with the night life of jazz—fast cars, sexual adventures, fine clothing. Persip talks about racing his Austin-Healey against Morgan’s Triumph; Heath mentions speeding late at night through Central Park. Shorter speaks of performing in night clubs and drinking double or triple cognacs between sets: “I would drink and have like a thin veil around me—that’s my space, my little dream space—and we would play.”

There were also drugs, and Morgan became addicted to heroin. Quickly, Morgan had practical troubles as a result. Morgan became unreliable and left Blakey’s band; he also hurt himself seriously, nodding out beside a radiator and burning the side of his head, giving himself a bald spot and a scar as a result, which he concealed with a sort of comb-over for the rest of his life. Shorter, who was close with Morgan, felt that he was slipping away; in the film, looking at a photo of Morgan with his head bandaged, he talks to the photo—“What you doing, man? Lee, what you doing?” Morgan pawned his clothing to buy drugs; Heath recalls Morgan saying that he’d prefer to get high rather than play music. Morgan couldn’t get work—and then he met Helen Morgan at her apartment, and she made him her project. She helped him get off drugs, she helped him get his career back together, she took care of the practical aspects of his work—and he was playing more daringly than ever. Then he started to see another woman—Judith Johnson, who discusses their relationship in the film—and the ultimate result was the violent showdown in Slug’s, on East Third Street.

Collin’s film brings out these stories with a wealth of details energized by the experiences and the insights of his interview subjects as well as an engaging range of archival images and clips. Some performances by Lee Morgan are also highlighted on the soundtrack, but, of course, in a ninety-minute film, it’s inevitably the music itself that gets shortest shrift. That’s no knock on the film but, rather, a reason to do some listening apart from it.

Morgan’s style of hard bop, a style launched by Blakey, Miles Davis, Horace Silver, and others in the mid-nineteen-fifties, was a kind of simplification of bebop—an infusion of blues in the place of some of bop’s harmonic complexity. The result was a musical paradox—on the one hand, some of the music (such as Blakey’s and Silver’s) leaned toward popularity, without musical compromise. On the other, the simplifications opened a new and freer kind of musical space for soloists, pulling other hard-boppers (such as Davis and Jackie McLean) in the direction of the avant-garde and free jazz. Morgan’s own career moved in both directions—he played often with Blakey—and he also played frequently with McLean, as well as with Bobby Hutcherson, Andrew Hill, and other progressive luminaries of the nineteen-sixties.

http://www.newyorker.com/culture/richard-brody/a-documentary-about-the-life-and-tragic-death-of-the-great-jazz-trumpeter-lee-morgan

I Called Him Morgan review – jazz star's story comes in from the cold

Kasper Collin’s spellbinding documentary reveals the tender and tragic tale of hard bop trumpeter Lee Morgan and his common-law wife Helen

Jordan Hoffman

The Guardian

Monday 12 September 2016

With the best jazz recordings you recognise the beginning and know where it’s going to wind up, but it’s the road there that’s unpredictable. To that end, Kasper Collin’s I Called Him Morgan isn’t just the greatest jazz documentary since Let’s Get Lost, it’s a documentary-as-jazz. Spellbinding, mercurial, hallucinatory, exuberant, tragic … aw hell, man, those are a lot of heavy words, but have you heard Lee Morgan’s music? More importantly, do you know the story of his life?

Lee Morgan may have been one of the most important trumpet players in jazz, but he doesn’t have the household name status of Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie or Miles Davis. Unfortunately, like Bix Beiderbecke and Clifford Brown, he died way too young. While Morgan’s output as the leader of his own working group is outstanding (may I recommend to you The Sidewinder, The Gigolo or perhaps even The Rumproller) he was also a linchpin member of the classic Blue Note sound overseen by producers Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff and engineer Rudy Van Gelder.

That’s Lee beside John Coltrane on the legendary 1957 album Blue Train. And that’s Lee as part of the Jazz Messengers, the supergroup led by drummer Art Blakey that ostensibly invented the subgenre known as hard bop. For those who don’t know much about jazz, this sound is what you think about when you think about jazz. And it’s Lee Morgan blowing the horn. And it’s Lee Morgan’s squeak at the 0:59 mark of Moanin’ that gives this art form its ineffable quality.

But I Called Him Morgan is far from a traditional documentary. Its story-within-a-story begins with a 2013 interview with Larry Reni Thomas, a North Carolina teacher who just so happens to be a legendary jazz DJ. In the mid 1990s, as he was greeting new students in an adult education class, he realised his new pupil (nearing age 70) was Helen Morgan, Lee’s widow. In 1996 Thomas sat down with an inexpensive tape recorder and asked her questions. A month later she died.

Collin turns to that plain, unlabelled white tape, marred by squeaks and hisses, and from it emerges the ghost of a voice. Helen Morgan was born in the 1920s in rural North Carolina, had two children out of wedlock at ages 13 and 14, then left for New York at 17 after her new husband passed away in an accident. She got a job at an answering service, and her apartment, located near all the jazz hotspots on West 53rd street, became something of a haven for musicians – mostly because she took pride in her cooking and was ready to feed anyone who came to her door.

At the same time, Lee Morgan was the young wonder on the scene. Collin traces his time with the Jazz Messengers using a deluge of remarkable photographs set to music. Commentary from Wayne Shorter, Tootie Heath, Larry Ridley and others offer insight, but not much can top the swirl of images. In 1964, Morgan recorded Search for the New Land (a precursor of sorts, I would argue, to the spiritual jazz of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme or Pharoah Sanders’s Karma) but, by that time, he had a debilitating drug addiction.

Lee and Helen finally collided in 1967. He was strung out and freezing on the street, and she brought him in from the cold. In Thomas’s audiotape, her recollection is so tender and so sad. “Why don’t you have a coat?” she repeats, in a thin, quaking voice.

Though 13 years his senior, she became his lover after being his nurse. Once he was cleaned up, they moved to the Bronx and he restarted his career, with her as his manager. But their relationship was not traditional. They were never formally married and Helen’s son, who was now back in the picture, was the same age as Lee. Though clean, one gets the impression Lee Morgan was still in a fog, and when he began a relationship with a new woman living in New Jersey, trouble began to mount.

I’m lucky to have spent many of my younger years as a jazz enthusiast in New York City and I swear to you it isn’t revisionist history that the music sounds better on snowy nights. Winter images (recreated on what appears to be 8mm) recur in I Called Him Morgan – snow outside the car window while passing the bridges surrounding Manhattan – and the film’s climax is inexorably linked to a horrible blizzard.

Though Lee and Helen Morgan’s fate is easily learned with a quick Google search, I’d rather leave it unspoken, out there in memory’s snowdrift, something strange and indescribable, like this sad but still beautiful film itself.

Monday 12 September 2016

With the best jazz recordings you recognise the beginning and know where it’s going to wind up, but it’s the road there that’s unpredictable. To that end, Kasper Collin’s I Called Him Morgan isn’t just the greatest jazz documentary since Let’s Get Lost, it’s a documentary-as-jazz. Spellbinding, mercurial, hallucinatory, exuberant, tragic … aw hell, man, those are a lot of heavy words, but have you heard Lee Morgan’s music? More importantly, do you know the story of his life?

Lee Morgan may have been one of the most important trumpet players in jazz, but he doesn’t have the household name status of Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie or Miles Davis. Unfortunately, like Bix Beiderbecke and Clifford Brown, he died way too young. While Morgan’s output as the leader of his own working group is outstanding (may I recommend to you The Sidewinder, The Gigolo or perhaps even The Rumproller) he was also a linchpin member of the classic Blue Note sound overseen by producers Alfred Lion and Francis Wolff and engineer Rudy Van Gelder.

That’s Lee beside John Coltrane on the legendary 1957 album Blue Train. And that’s Lee as part of the Jazz Messengers, the supergroup led by drummer Art Blakey that ostensibly invented the subgenre known as hard bop. For those who don’t know much about jazz, this sound is what you think about when you think about jazz. And it’s Lee Morgan blowing the horn. And it’s Lee Morgan’s squeak at the 0:59 mark of Moanin’ that gives this art form its ineffable quality.

But I Called Him Morgan is far from a traditional documentary. Its story-within-a-story begins with a 2013 interview with Larry Reni Thomas, a North Carolina teacher who just so happens to be a legendary jazz DJ. In the mid 1990s, as he was greeting new students in an adult education class, he realised his new pupil (nearing age 70) was Helen Morgan, Lee’s widow. In 1996 Thomas sat down with an inexpensive tape recorder and asked her questions. A month later she died.

Collin turns to that plain, unlabelled white tape, marred by squeaks and hisses, and from it emerges the ghost of a voice. Helen Morgan was born in the 1920s in rural North Carolina, had two children out of wedlock at ages 13 and 14, then left for New York at 17 after her new husband passed away in an accident. She got a job at an answering service, and her apartment, located near all the jazz hotspots on West 53rd street, became something of a haven for musicians – mostly because she took pride in her cooking and was ready to feed anyone who came to her door.

At the same time, Lee Morgan was the young wonder on the scene. Collin traces his time with the Jazz Messengers using a deluge of remarkable photographs set to music. Commentary from Wayne Shorter, Tootie Heath, Larry Ridley and others offer insight, but not much can top the swirl of images. In 1964, Morgan recorded Search for the New Land (a precursor of sorts, I would argue, to the spiritual jazz of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme or Pharoah Sanders’s Karma) but, by that time, he had a debilitating drug addiction.

Lee and Helen finally collided in 1967. He was strung out and freezing on the street, and she brought him in from the cold. In Thomas’s audiotape, her recollection is so tender and so sad. “Why don’t you have a coat?” she repeats, in a thin, quaking voice.

Though 13 years his senior, she became his lover after being his nurse. Once he was cleaned up, they moved to the Bronx and he restarted his career, with her as his manager. But their relationship was not traditional. They were never formally married and Helen’s son, who was now back in the picture, was the same age as Lee. Though clean, one gets the impression Lee Morgan was still in a fog, and when he began a relationship with a new woman living in New Jersey, trouble began to mount.

I’m lucky to have spent many of my younger years as a jazz enthusiast in New York City and I swear to you it isn’t revisionist history that the music sounds better on snowy nights. Winter images (recreated on what appears to be 8mm) recur in I Called Him Morgan – snow outside the car window while passing the bridges surrounding Manhattan – and the film’s climax is inexorably linked to a horrible blizzard.

Though Lee and Helen Morgan’s fate is easily learned with a quick Google search, I’d rather leave it unspoken, out there in memory’s snowdrift, something strange and indescribable, like this sad but still beautiful film itself.

Tuesday, 18 April 2017

Monday, 17 April 2017

Sunday, 16 April 2017

Paddy McAloon, Jarvis Cocker and others on trawling the megahertz

I thought I'd use this one again! Jack Kirby AND Paddy McAloon. Can't be bad.

Jarvis Cocker navigates the ether as he continues his nocturnal exploration of the human condition.

On a night voyage across a sea of shortwave he meets those who broadcast, monitor and harvest electronic radio transmissions after dark.

Paddy McAloon, founder of the band Prefab Sprout, took to trawling the megahertz when he was recovering from eye surgery and the world around him became dark. Tuning in at night he developed a ghostly romance with far off voices and abnormal sounds.

Artist Katie Paterson and 'Moonbouncer' Peter Blair send Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata to the moon and back, to find sections of it swallowed up by craters.

Journalist Colin Freeman was captured by the Somali pirates he went to report on and held hostage in a cave. But when one of them loaned him a shortwave radio, the faint signal to the outside world gave him hope as he dreamed of freedom.

And "London Shortwave" hides out in a park after dark, with his ear to the speaker on his radio, slowly turning the dial to reach all four corners of the earth

Jarvis sails in and out of their stories - from the cosmic to the captive - as he wonders what else is out there, deep in the noise

Producer Neil McCarthy.

Listen now - http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b08k1y9j

Meanwhile, rumours once more circulate - about a year after they last did - that Paddy's I Trawl the Megahertz will be released in all formats but credited to Prefab Sprout this time...

I read it here first: http://www.sproutology.co.uk/sproutbait/more-trawling-of-the-megahertz/

Saturday, 15 April 2017

Friday, 14 April 2017

Dead Poets Society #34 Alan Dugan: Fabrication of Ancestors

Fabrication of Ancestors by Alan Dugan

FOR OLD BILLY DUGAN, SHOT IN THE ASS IN THE CIVIL WAY, MY FATHER SAID

The old wound in my ass

has opened up again, but I

am past the prodigies

of youth’s campaigns, and weep

where I used to laugh

in war’s red humors, half

in love with silly-assed pains

and half not feeling them.

I have to sit up with

an indoor unsittable itch

before I go down late

and weeping to the storm-

cellar on a dirty night

and go to bed with the worms.

So pull the dirt up over me

and make a family joke

for Old Billy Blue Balls,

the oldest private in the world

with two ass-holes and no

place more to go to for a laugh

except the last one. Say:

The North won the Civil War

without much help from me

although I wear a proof

of the war’s obscenity.

Thursday, 13 April 2017

Last night's set lists

At The Habit, York: -

Da Elderly: -

Out On The Weekend

In The Morning Light

I Believe In You

Ron Elderly: -

Streets Of London

One More Cup Of Coffee

Just My Imagination

The Elderly Brothers (1): -

Dead Flowers

Yes I Will

Medley: Sweet Caroline/Hi Ho Silver Lining

The Elderly Brothers(2): -

You Really Got A Hold On Me

The Price Of Love

All I Have To Do Is Dream

A very quiet night for once and the Chinese was shut, so not a great start to proceedings! A shortage of performers meant we got a third song each and Ron debuted a Bobsong from Desire. After the second round of 'turns' had been completed there was just time for the Elderlys to finish off the night with a couple of Phil & Don classics. It turned out to be a very enjoyable evening in the end, with post-show banter finally coming to a close around 1am.

Da Elderly: -

Out On The Weekend

In The Morning Light

I Believe In You

Ron Elderly: -

Streets Of London

One More Cup Of Coffee

Just My Imagination

The Elderly Brothers (1): -

Dead Flowers

Yes I Will

Medley: Sweet Caroline/Hi Ho Silver Lining

The Elderly Brothers(2): -

You Really Got A Hold On Me

The Price Of Love

All I Have To Do Is Dream

A very quiet night for once and the Chinese was shut, so not a great start to proceedings! A shortage of performers meant we got a third song each and Ron debuted a Bobsong from Desire. After the second round of 'turns' had been completed there was just time for the Elderlys to finish off the night with a couple of Phil & Don classics. It turned out to be a very enjoyable evening in the end, with post-show banter finally coming to a close around 1am.

Wednesday, 12 April 2017

Tuesday, 11 April 2017

Monday, 10 April 2017

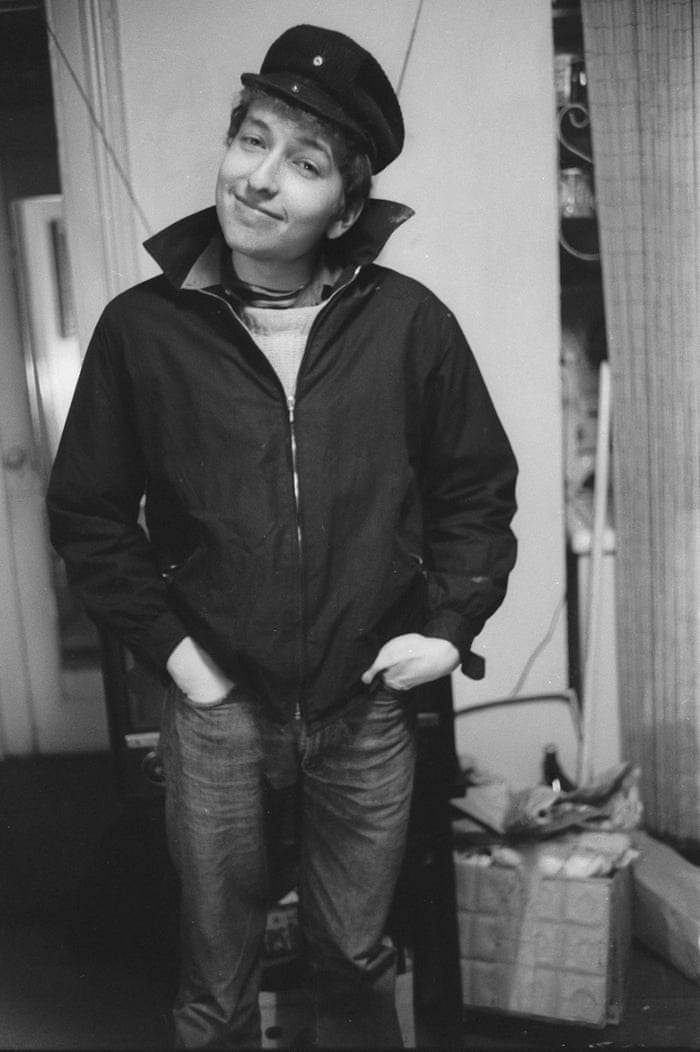

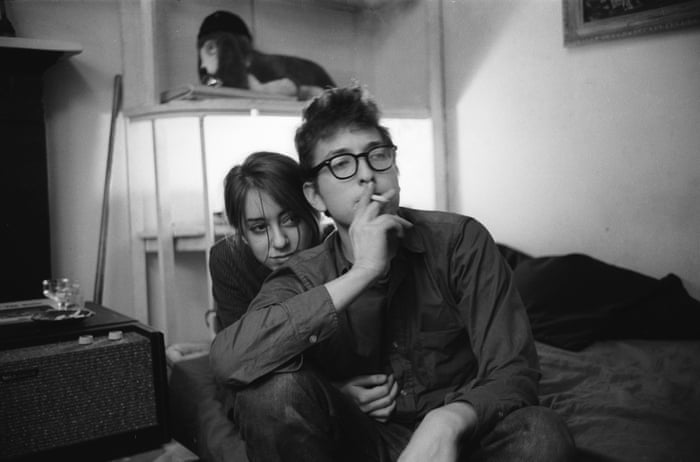

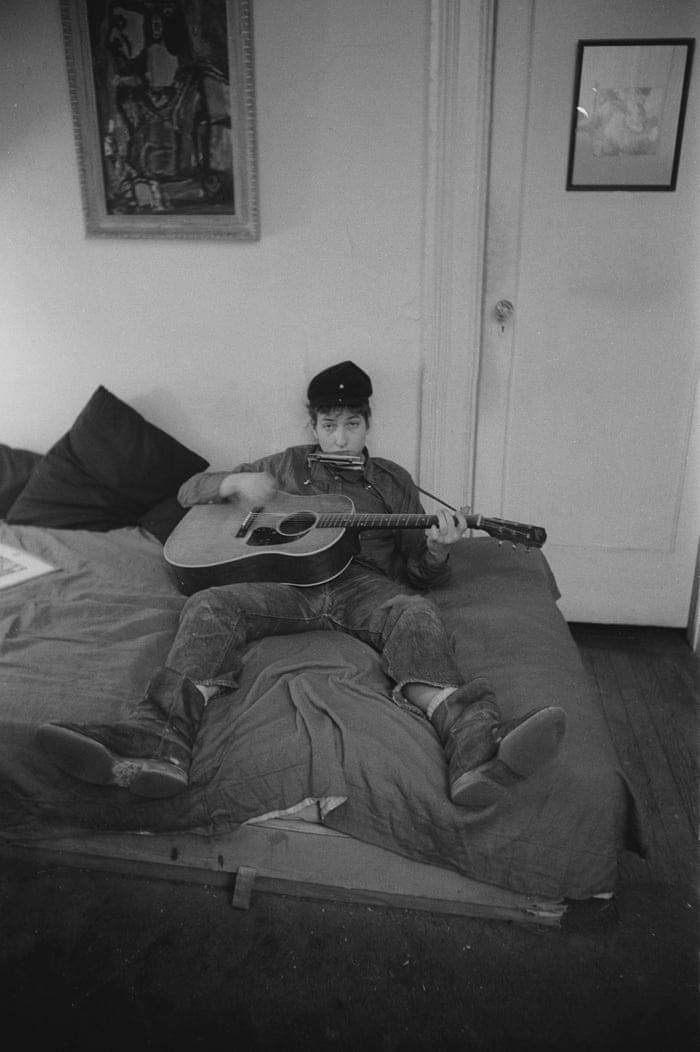

Bob Dylan in New York City, 1961 - 1964 by Ted Russell

Portraits of a young Bob Dylan

As Bob Dylan accepts his Nobel prize for literature this weekend, an exhibition of photographs of him on the cusp of international fame is planned to open in New York. The photographer Ted Russell first met Dylan in 1961 and his intimate pictures of Dylan performing, and at home, are the subject of a show at the Steven Kasher Gallery featuring dozens of images never before seen in the city. Bob Dylan NYC 1961–1964 opens on 20 April and will run until 3 June.

Dylan at his typewriter

Bob Dylan and James Baldwin talking at the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee’s Bill of Rights dinner to present Dylan with the Tom Paine Award

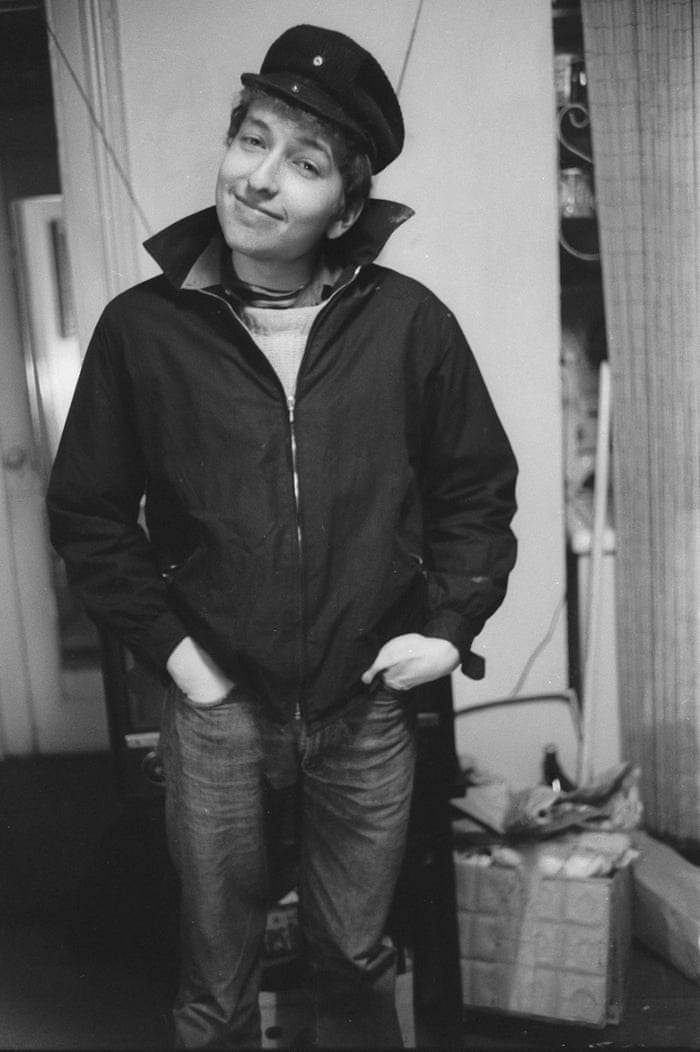

Dylan at home in New York City

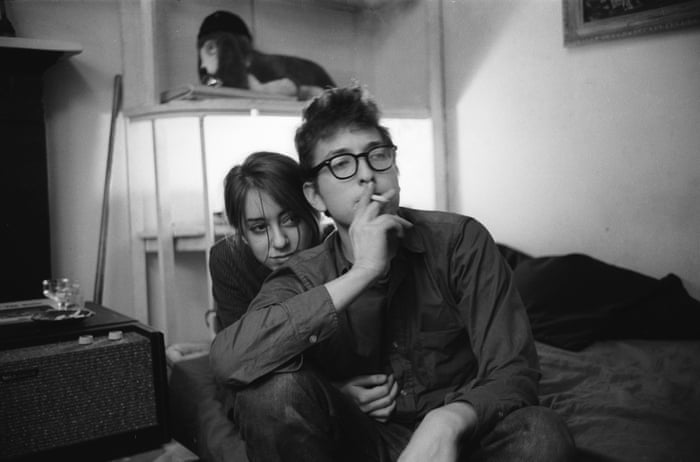

Dylan and Suze Rotolo in his Greenwich Village apartment

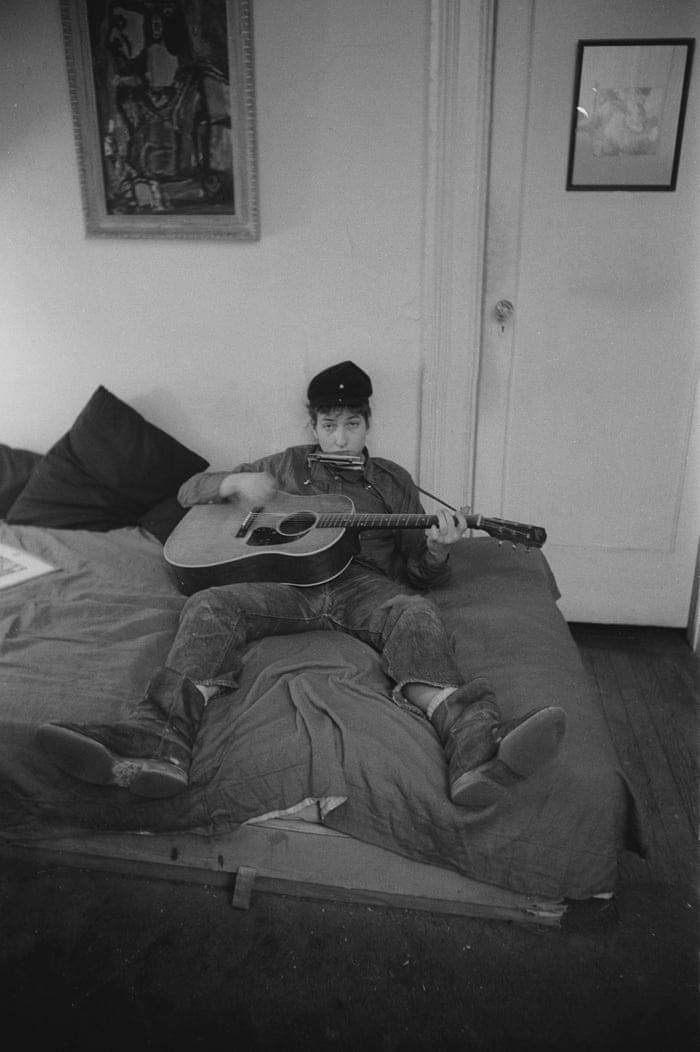

Playing harmonica and guitar in his apartment

On stage

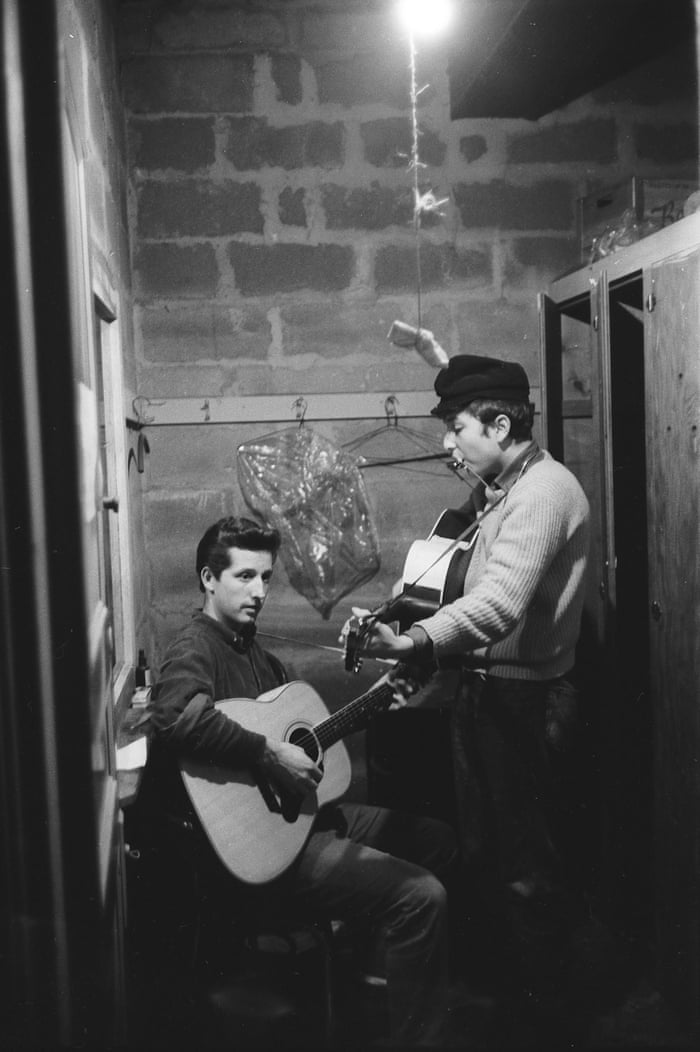

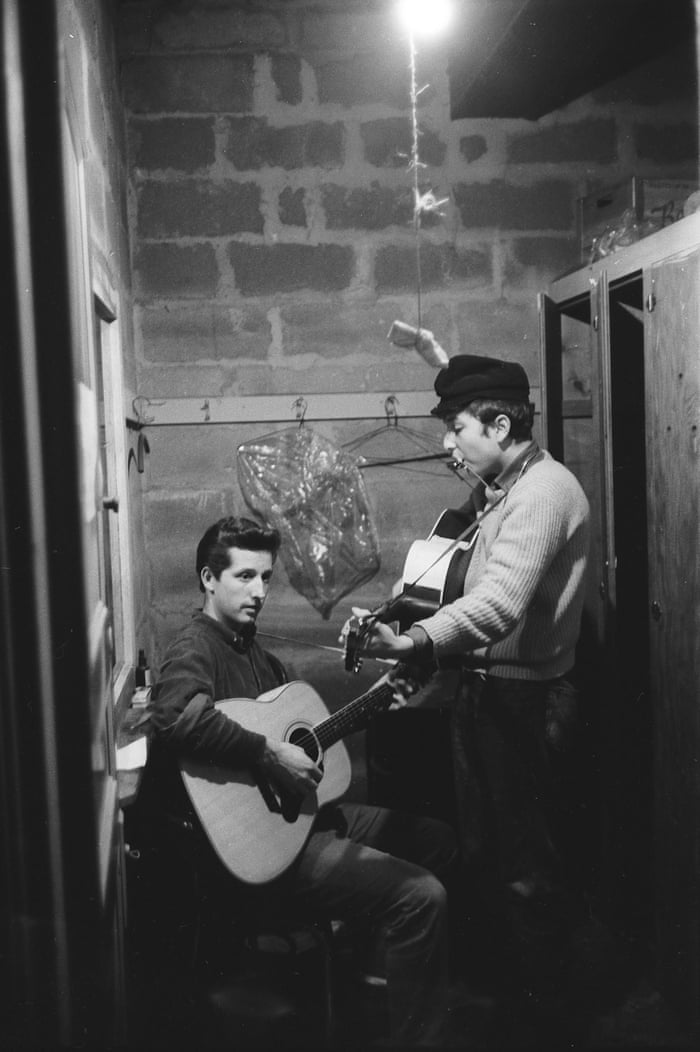

Bob Dylan with Mark Spoelstra in the basement at Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village

Dylan at his good old desk

Ted Russell: Bob Dylan NYC 1961-1964

Exhibition: April 20th – June 3rd, 2017

Opening Reception: Thursday, April 20th, 6-8PM

Steven Kasher Gallery is pleased to present Ted Russell: Bob Dylan NYC 1961-1964, an exhibition of exceptionally early photographs of the 2016 Nobel Laureate in Literature. Russell, a New York based photographer still living in Forest Hills, depicts Dylan at key moments that established him as one of America’s greatest artists. He performs one of his earliest gigs, makes music and love in his first New York apartment with his first and most important muse, receives his first public award (in the company of James Baldwin) and writes some of his earliest songs. The exhibition features 40 black and white prints of recently discovered images never before exhibited in New York. The exhibition is accompanied by the 2015 Rizzoli book of the same title.

In November of 1961, Bob Dylan was 20 years old, a folk singer on the cusp. His first paid performances, mostly at Gerde’s Folk City, were attracting interest. His first review was just out, a surprising rave in the New York Times, which said “Mr. Dylan is both a comedian and a tragedian.” John Hammond was in the process of signing him to a major label and recording his first demo tapes. This included his first breakthrough original composition, “Song for Woody,” a song more contemporary and personal than any of its time and the template for all the singer-songwriter music of the 1960s and beyond.

In November of 1961, Ted Russell was a young photographer who had had a few pictures published in Life. An RCA records publicist asked him to make a portrait of their latest discovery, a still-unknown Ann-Margaret. Shortly after, the RCA publicist moved to Columbia Records and invited Russell to take some pictures of their new hire, Bob Dylan. Russell liked the idea, thinking a story on an up-and-coming Village folksinger could interest Life.

Russell first shot Dylan singing at Folk City. The next day he shot Dylan with his girlfriend, Suze Rotolo in their walk-up brownstone apartment at 161 West 4th Street. Rotolo worked for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and for SANE (The Committee for a SANE Nuclear Policy). Dylan first wrote civil rights and anti-nuclear war songs under her influence and called her “the most erotic thing I’d ever seen.” In this 1961 set Dylan is adolescent, smooth, relaxed. He pretends to be unaware of the camera, but clearly basks in its gaze. On stage and off, he is a performer, a charmer of great suavity. He plays guitar and harmonica on stage, and on and off the mattress on the apartment floor. He takes his glasses on and off. He fiddles with Rotolo, who the camera also loves. The apartment is full of endearing personal effects: a wicker trimmed phonograph, a stuffed beagle, wine bottles on the floor, a framed reproduction of Roualt’s “The Old King”.

In December of 1963, shortly after the assassination of JFK, Russell photographed Dylan and James Baldwin for Life as Dylan received the Tom Paine award from the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee. In a speech at the reception Dylan scandalized the audience by saying “Lee Harvey Oswald… I saw some of myself in him.” Baldwin’s affection for Dylan is manifest in his broad smile, and Dylan seems to reciprocate.

In 1964, again on assignment for Life, Russell photographed Dylan in his same Village apartment. Rotolo had broken up with Dylan, inspiring “Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright” and other great ballads. The Roualt on the wall has been replaced by the framed Tom Paine award. Dylan has traded in his guitar and harmonica for a typewriter and a telephone. By now Dylan is a recording star, and has written some of the most important songs of the century. He is older, more anxious. Russell even portrays him as a silhouette looking out a window, a classic pose for a dignitary in deep thought.

Ted Russell was born in London in 1930. He began photographing at age 10, and by age 15 was apprenticing in London's Fleet Street. The following year he worked as a stringer photographer for Acme Newspictures in Brussels. He later joined the staff of Now, an English language picture magazine, and then U.S. Army's Spotlight magazine. In 1952 he boarded the Queen Mary for New York, arriving with four cameras and $200. He was soon drafted and served as unit photographer with the U.S. Army's 2nd Engineers in the Korean War. After attending the University of California at Berkeley, he returned to New York and became a contributing photographer for Life magazine for over 12 years, shooting hundreds of domestic and overseas assignments. Later Russell did numerous advertising campaigns before ending up as Cover Photo Editor of Newsweek magazine for 11 years. His work has appeared in Life, Newsweek, Time, Saturday Review and New York magazines. His photographs have been exhibited at the International Center of Photography and Museum of Modern Art.

Ted Russell: Bob Dylan NYC 1961-1964 will be on view April 20 – June 3, 2017. Steven Kasher Gallery is located at 515 W. 26th St., New York, NY 10001. Gallery hours are Tuesday through Saturday, 10 AM to 6 PM. For press and all other inquiries, please contact Cassandra Johnson, 212 966 3978, cassandra@stevenkasher.com.

http://www.stevenkasher.com/exhibitions/ted-russell-bob-dylan-nyc-1961-1964

Sarah Gilbert

The Guardian

Saturday 1 April 2017

As Bob Dylan accepts his Nobel prize for literature this weekend, an exhibition of photographs of him on the cusp of international fame is planned to open in New York. The photographer Ted Russell first met Dylan in 1961 and his intimate pictures of Dylan performing, and at home, are the subject of a show at the Steven Kasher Gallery featuring dozens of images never before seen in the city. Bob Dylan NYC 1961–1964 opens on 20 April and will run until 3 June.

Dylan at his typewriter

Bob Dylan and James Baldwin talking at the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee’s Bill of Rights dinner to present Dylan with the Tom Paine Award

Dylan at home in New York City

Dylan and Suze Rotolo in his Greenwich Village apartment

Playing harmonica and guitar in his apartment

On stage

Bob Dylan with Mark Spoelstra in the basement at Gerde’s Folk City in Greenwich Village

Dylan at his good old desk

Ted Russell: Bob Dylan NYC 1961-1964

Exhibition: April 20th – June 3rd, 2017

Opening Reception: Thursday, April 20th, 6-8PM

Steven Kasher Gallery is pleased to present Ted Russell: Bob Dylan NYC 1961-1964, an exhibition of exceptionally early photographs of the 2016 Nobel Laureate in Literature. Russell, a New York based photographer still living in Forest Hills, depicts Dylan at key moments that established him as one of America’s greatest artists. He performs one of his earliest gigs, makes music and love in his first New York apartment with his first and most important muse, receives his first public award (in the company of James Baldwin) and writes some of his earliest songs. The exhibition features 40 black and white prints of recently discovered images never before exhibited in New York. The exhibition is accompanied by the 2015 Rizzoli book of the same title.

In November of 1961, Bob Dylan was 20 years old, a folk singer on the cusp. His first paid performances, mostly at Gerde’s Folk City, were attracting interest. His first review was just out, a surprising rave in the New York Times, which said “Mr. Dylan is both a comedian and a tragedian.” John Hammond was in the process of signing him to a major label and recording his first demo tapes. This included his first breakthrough original composition, “Song for Woody,” a song more contemporary and personal than any of its time and the template for all the singer-songwriter music of the 1960s and beyond.

In November of 1961, Ted Russell was a young photographer who had had a few pictures published in Life. An RCA records publicist asked him to make a portrait of their latest discovery, a still-unknown Ann-Margaret. Shortly after, the RCA publicist moved to Columbia Records and invited Russell to take some pictures of their new hire, Bob Dylan. Russell liked the idea, thinking a story on an up-and-coming Village folksinger could interest Life.

Russell first shot Dylan singing at Folk City. The next day he shot Dylan with his girlfriend, Suze Rotolo in their walk-up brownstone apartment at 161 West 4th Street. Rotolo worked for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and for SANE (The Committee for a SANE Nuclear Policy). Dylan first wrote civil rights and anti-nuclear war songs under her influence and called her “the most erotic thing I’d ever seen.” In this 1961 set Dylan is adolescent, smooth, relaxed. He pretends to be unaware of the camera, but clearly basks in its gaze. On stage and off, he is a performer, a charmer of great suavity. He plays guitar and harmonica on stage, and on and off the mattress on the apartment floor. He takes his glasses on and off. He fiddles with Rotolo, who the camera also loves. The apartment is full of endearing personal effects: a wicker trimmed phonograph, a stuffed beagle, wine bottles on the floor, a framed reproduction of Roualt’s “The Old King”.

In December of 1963, shortly after the assassination of JFK, Russell photographed Dylan and James Baldwin for Life as Dylan received the Tom Paine award from the Emergency Civil Liberties Committee. In a speech at the reception Dylan scandalized the audience by saying “Lee Harvey Oswald… I saw some of myself in him.” Baldwin’s affection for Dylan is manifest in his broad smile, and Dylan seems to reciprocate.

In 1964, again on assignment for Life, Russell photographed Dylan in his same Village apartment. Rotolo had broken up with Dylan, inspiring “Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright” and other great ballads. The Roualt on the wall has been replaced by the framed Tom Paine award. Dylan has traded in his guitar and harmonica for a typewriter and a telephone. By now Dylan is a recording star, and has written some of the most important songs of the century. He is older, more anxious. Russell even portrays him as a silhouette looking out a window, a classic pose for a dignitary in deep thought.

Ted Russell was born in London in 1930. He began photographing at age 10, and by age 15 was apprenticing in London's Fleet Street. The following year he worked as a stringer photographer for Acme Newspictures in Brussels. He later joined the staff of Now, an English language picture magazine, and then U.S. Army's Spotlight magazine. In 1952 he boarded the Queen Mary for New York, arriving with four cameras and $200. He was soon drafted and served as unit photographer with the U.S. Army's 2nd Engineers in the Korean War. After attending the University of California at Berkeley, he returned to New York and became a contributing photographer for Life magazine for over 12 years, shooting hundreds of domestic and overseas assignments. Later Russell did numerous advertising campaigns before ending up as Cover Photo Editor of Newsweek magazine for 11 years. His work has appeared in Life, Newsweek, Time, Saturday Review and New York magazines. His photographs have been exhibited at the International Center of Photography and Museum of Modern Art.

Ted Russell: Bob Dylan NYC 1961-1964 will be on view April 20 – June 3, 2017. Steven Kasher Gallery is located at 515 W. 26th St., New York, NY 10001. Gallery hours are Tuesday through Saturday, 10 AM to 6 PM. For press and all other inquiries, please contact Cassandra Johnson, 212 966 3978, cassandra@stevenkasher.com.

http://www.stevenkasher.com/exhibitions/ted-russell-bob-dylan-nyc-1961-1964

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)