Michael Powell

17 November 2017

Frank Black

I was lucky. My film tutor, the wonderful Charles Barr, introduced me to Powell and Pressburger through A Canterbury Tale (1944), a film so magical that it knocked a bunch of cynical 19 year-olds off our feet and it was all we could talk about for weeks. It left a indelible imprint and I sought out their other films, all of which I love, even if I did have to overcome the considerable barrier of Laurence Olivier's ham acting as a French-Canadian trapper in 49th Parallel (1941), where he is totally overshadowed by a beautifully understated performance from Niall McGinnis as a sympathetic German who opts to stay and help a local Hutterite farming community and is executed by his commander played by Eric Portman.

Although Powell continued to make films afterwards, it was his controversial psychological thriller, Peeping Tom (1960), made without his partner Emeric Pressburger, that turned opinion against him - that and, perhaps, the fad amongst middle class critics for the social realist genre of British 'working class' cinema of the late 1950s - 1960s. Fortunately, like Powell, the film has been rehabilitated; it was voted number 78 in the list of 100 great British films of all time in a survey by the British Film Institute - though there are some fairly odd choices above it (Withnail and I, Life of Brian, Four Weddings and a Funeral, spring to mind). Of course, it's probably better not to examine such lists in too much detail: there are only two films by Hitchcock on it, after all!

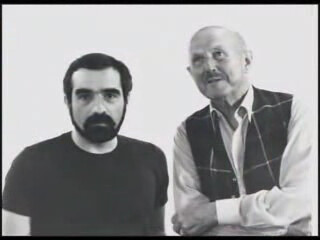

Anyhow, here's a short radio documentary about Powell and his relationship with Martin Scorsese, who explains that he not only admired him but felt in debt to his work. Fighting to bring to bring Powell's work to the world's attention at a time when many people (audiences, critics and cinephiles alike) seemed to have forgotten him, he highlighted just how a significant a film-maker he was and helped re-establish his reputation.

During this period, Powell married Thelma Schoonmaker, Scorsese's editor, and she talks eloquently of the friendship between the two men.

I'm pleased to say, A Canterbury Tale features heavily.

It's on BBC iPlayer, which means you'll have to sign up for a free account!

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0076shd?p_f_added=urn%3Abbc%3Aradio%3Aprogramme%3Ab0076shd%3Atitle%3DMichael%2520and%2520Martin

Scorsese: my friendship with Michael Powell

He fell in love with The Red Shoes aged nine - now Martin Scorsese is bringing a glorious new print to Cannes. He talks about his debt to its director

Steve Rose

The Guardian

Thursday 14 May 2009

"Movie directors are desperate people. You're totally desperate every second of the day when you're involved in a film, through pre-production, production, post-production, and certainly when you're dealing with the press." Martin Scorsese isn't talking about his own career, but that of one of his heroes, the British director Michael Powell. And in particular, Scorsese is referring to the all-consuming creative passion Powell and Emeric Pressburger captured in their 1948 classic The Red Shoes. That swooning Technicolor tragedy was ostensibly set in the world of ballet, with Moira Shearer fatally torn between her personal and professional loyalties; equally, it is a portrait of artistic sacrifice and compromise in the film-makers' own industry. "Over the years, what's really stayed in my mind and my heart is the dedication those characters had, the nature of that power and the obsession to create," Scorsese says, before finding the right analogy in another Powell and Pressburger title: "It made it a matter of life and death, really."

Had he not been so entranced by The Red Shoes as a boy, Scorsese might never have become a movie director. Watching the film for the first time - aged nine, at the cinema with his father - was the start of a lifelong relationship with Powell's movies, one that ultimately led to a friendship with the man himself; now, nearly 20 years after Powell's death, it extends to a stewardship of his legacy. Tomorrow, Scorsese will take the stage in Cannes to introduce a new restored print of The Red Shoes - a culmination, of sorts, to Scorsese's ongoing mission to rehabilitate his hero. Scorsese was instrumental not just in initiating the physical restoration of Powell and Pressburger's deteriorating back catalogue, but in restoring Powell's career and reputation when they were at their lowest ebb. He even, inadvertently, found him a wife.

Scorsese considers Powell and Pressburger's run of films through the 1930s and 40s to be "the longest period of subversive film-making in a major studio, ever". But when Scorsese first met Powell, in 1975, that run had come to an abrupt halt. Peeping Tom, Powell's first effort as a solo director, had been released in 1960, and its combination of violence, voyeurism, nudity and general implication of the audience (not to mention the film industry, again) was too strong for the British censors and critics. So he must have been somewhat taken aback to discover that an eager young American director was trying to track him down, and that other young American film-makers were going back to his work.

"We'd been asking for years about Powell and Pressburger," says Scorsese. "There was hardly anything written about their films at that time. We wondered how the same man who made A Matter of Life and Death, The Red Shoes, Black Narcissus, and The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp could also have made Peeping Tom. We actually thought for a while Michael Powell was a pseudonym being used by other film-makers."

Scorsese came to Britain for the Edinburgh film festival with Taxi Driver, and a mutual contact arranged a meeting at a London restaurant. "He was very quiet and didn't quite know what to make of me," Scorsese recalls. "I had to explain to him that his work was a great source of inspiration for a whole new generation of film-makers - myself, Spielberg, Paul Schrader, Coppola, De Palma. We would talk about his films in Los Angeles often. They were a lifeblood to us, at a time when the films were not necessarily immediately available. He had no idea this was all happening."

It's easy to forget how obscure most movies were in the days before DVD, video on demand, or even VHS. Studio boss J Arthur Rank lost faith in the commercial potential of The Red Shoes on first seeing it, and sent only a single print to the US. So for two years it played continuously at a single movie theatre in New York, before eventually breaking out to become a huge success, picking up Oscars in 1949 for best art direction and music. Scorsese saw it that first time in colour; after that, the only way to see such movies was on television. "Even with commercial breaks, in black and white, and cut to about an hour and a half, it still had a powerful magic," he says. "The vibrancy of the movie and the sense of colour in the storytelling actually came through. Then, eventually, the prize was to track down a 16mm Technicolor print. I was able to do that a few times." The rest of the Powell/Pressburger back catalogue Scorsese would track down one film at a time. "We were in a process of discovery."

After Scorsese found him, Powell was taken to the US by Francis Ford Coppola and feted by his new Hollywood fans. They saw him as a kindred spirit: a fiercely independent film-maker who had fought for, and justified, the need for complete creative freedom. Coppola installed him as senior director-in-residence at his Zoetrope studios; he took teaching posts; retrospectives were held of his work; and the great and good of Hollywood queued up to meet him. Scorsese even had a cossack shirt made in the same style as that of Anton Walbrook's character in The Red Shoes, which he wore to the opening of Powell and Pressburger's 1980 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. To that event, Scorsese brought along his editor on Raging Bull, Thelma Schoonmaker. "Marty told me I had to go and see Colonel Blimp on the big screen," Schoonmaker later tells me. She introduced herself to Powell, they hit it off, and four years later they married.

Schoonmaker, who still edits all Scorsese's films, experienced first-hand both Scorsese's worship of Powell and his subsequent friendship with him. "One of the first things Marty said to me was, 'I've just discovered a new Powell and Pressburger masterpiece!' We were working at night on Raging Bull and he said, 'You have to come into the living room and look at this right now.' He had a videocassette of I Know Where I'm Going. For him to have taken an hour and a half out of our editing time is typical of the way he proselytises. Anyone he meets, or the actors he works with, he immediately starts bombarding with Powell and Pressburger movies."

Powell's influence is all over Scorsese's work. His trademark use of the colour red is a direct homage to Powell, for example - though Powell told him he overused the colour in Mean Streets. And Powell was practically a consultant on Raging Bull, giving Scorsese script advice and even guiding him towards releasing the film in black and white. (Again, Powell observed that Robert de Niro's boxing gloves were too red.) Meanwhile, Powell's Tales of Hoffman informed the movements of Raging Bull's fight scenes. "Marty was always asking Michael, 'How did you do that shot?' or 'Where did you get that idea?'" Schoonmaker says. "They shared a tremendous passion for the history of film - but he didn't always go along with Marty's taste in modern film-makers. For example, Michael didn't quite get Sam Fuller. Marty showed him Forty Guns, or started to show it to him, and Michael walked out halfway through. Marty was heartbroken."

The restoration of The Red Shoes came about when Schoonmaker tried to buy Scorsese a print of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp for his 60th birthday. She was alarmed to discover the printing negative was worn out, and that there wasn't enough money to restore it. Much of the Powell and Pressburger legacy was, and still is, in a similar condition. So she and Scorsese set about raising the cash to fund the restoration. "It's been over two years now of checking test prints and determining how the picture should be restored," says Scorsese. "In restoration circles, very often three-strip Technicolor film can only reach a certain technical level. The colours start to become yellow and you get fringing - where the strips don't quite line up. But the techniques we used here are top of the line. So it looks better than new. It's exactly like what the film-makers wanted at the time, but they couldn't achieve it back then."

Other Powell/Pressburger movies are now in line for restoration, but Scorsese and Schoonmaker's rehabilitation mission does not stop there. For some years, between movie projects (they are currently completing Scorsese's latest, Shutter Island, with Leonardo DiCaprio), they have been working on a documentary about British cinema, in the vein of Scorsese's 1999 personal appreciation of Italian cinema, My Voyage in Italy. Powell and Pressburger will be in there of course; but also Hitchcock, Korda, Anthony Asquith and possibly others we've forgotten about ourselves. British cinema is sorely misunderstood, Scorsese feels, and it needs this documentary even more than Italian cinema did.

Perhaps that's something for next year's Cannes? "Well, I'm still working on my speech [for Friday]," says Scorsese. "I never know what to say. I'm trying to hone it down to my key emotional connection to the film. My favourite scene is the one near the beginning at the cocktail party. Where Lermontov [Anton Walbrook] asks Vicky [Moira Shearer], 'Why do you want to dance?' and she replies, 'Why do you want to live?' Despite all the other beautiful sequences in the film, that's the one that stays in my mind."

Thursday 14 May 2009

"Movie directors are desperate people. You're totally desperate every second of the day when you're involved in a film, through pre-production, production, post-production, and certainly when you're dealing with the press." Martin Scorsese isn't talking about his own career, but that of one of his heroes, the British director Michael Powell. And in particular, Scorsese is referring to the all-consuming creative passion Powell and Emeric Pressburger captured in their 1948 classic The Red Shoes. That swooning Technicolor tragedy was ostensibly set in the world of ballet, with Moira Shearer fatally torn between her personal and professional loyalties; equally, it is a portrait of artistic sacrifice and compromise in the film-makers' own industry. "Over the years, what's really stayed in my mind and my heart is the dedication those characters had, the nature of that power and the obsession to create," Scorsese says, before finding the right analogy in another Powell and Pressburger title: "It made it a matter of life and death, really."

Had he not been so entranced by The Red Shoes as a boy, Scorsese might never have become a movie director. Watching the film for the first time - aged nine, at the cinema with his father - was the start of a lifelong relationship with Powell's movies, one that ultimately led to a friendship with the man himself; now, nearly 20 years after Powell's death, it extends to a stewardship of his legacy. Tomorrow, Scorsese will take the stage in Cannes to introduce a new restored print of The Red Shoes - a culmination, of sorts, to Scorsese's ongoing mission to rehabilitate his hero. Scorsese was instrumental not just in initiating the physical restoration of Powell and Pressburger's deteriorating back catalogue, but in restoring Powell's career and reputation when they were at their lowest ebb. He even, inadvertently, found him a wife.

Scorsese considers Powell and Pressburger's run of films through the 1930s and 40s to be "the longest period of subversive film-making in a major studio, ever". But when Scorsese first met Powell, in 1975, that run had come to an abrupt halt. Peeping Tom, Powell's first effort as a solo director, had been released in 1960, and its combination of violence, voyeurism, nudity and general implication of the audience (not to mention the film industry, again) was too strong for the British censors and critics. So he must have been somewhat taken aback to discover that an eager young American director was trying to track him down, and that other young American film-makers were going back to his work.

"We'd been asking for years about Powell and Pressburger," says Scorsese. "There was hardly anything written about their films at that time. We wondered how the same man who made A Matter of Life and Death, The Red Shoes, Black Narcissus, and The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp could also have made Peeping Tom. We actually thought for a while Michael Powell was a pseudonym being used by other film-makers."

Scorsese came to Britain for the Edinburgh film festival with Taxi Driver, and a mutual contact arranged a meeting at a London restaurant. "He was very quiet and didn't quite know what to make of me," Scorsese recalls. "I had to explain to him that his work was a great source of inspiration for a whole new generation of film-makers - myself, Spielberg, Paul Schrader, Coppola, De Palma. We would talk about his films in Los Angeles often. They were a lifeblood to us, at a time when the films were not necessarily immediately available. He had no idea this was all happening."

It's easy to forget how obscure most movies were in the days before DVD, video on demand, or even VHS. Studio boss J Arthur Rank lost faith in the commercial potential of The Red Shoes on first seeing it, and sent only a single print to the US. So for two years it played continuously at a single movie theatre in New York, before eventually breaking out to become a huge success, picking up Oscars in 1949 for best art direction and music. Scorsese saw it that first time in colour; after that, the only way to see such movies was on television. "Even with commercial breaks, in black and white, and cut to about an hour and a half, it still had a powerful magic," he says. "The vibrancy of the movie and the sense of colour in the storytelling actually came through. Then, eventually, the prize was to track down a 16mm Technicolor print. I was able to do that a few times." The rest of the Powell/Pressburger back catalogue Scorsese would track down one film at a time. "We were in a process of discovery."

After Scorsese found him, Powell was taken to the US by Francis Ford Coppola and feted by his new Hollywood fans. They saw him as a kindred spirit: a fiercely independent film-maker who had fought for, and justified, the need for complete creative freedom. Coppola installed him as senior director-in-residence at his Zoetrope studios; he took teaching posts; retrospectives were held of his work; and the great and good of Hollywood queued up to meet him. Scorsese even had a cossack shirt made in the same style as that of Anton Walbrook's character in The Red Shoes, which he wore to the opening of Powell and Pressburger's 1980 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. To that event, Scorsese brought along his editor on Raging Bull, Thelma Schoonmaker. "Marty told me I had to go and see Colonel Blimp on the big screen," Schoonmaker later tells me. She introduced herself to Powell, they hit it off, and four years later they married.

Schoonmaker, who still edits all Scorsese's films, experienced first-hand both Scorsese's worship of Powell and his subsequent friendship with him. "One of the first things Marty said to me was, 'I've just discovered a new Powell and Pressburger masterpiece!' We were working at night on Raging Bull and he said, 'You have to come into the living room and look at this right now.' He had a videocassette of I Know Where I'm Going. For him to have taken an hour and a half out of our editing time is typical of the way he proselytises. Anyone he meets, or the actors he works with, he immediately starts bombarding with Powell and Pressburger movies."

Powell's influence is all over Scorsese's work. His trademark use of the colour red is a direct homage to Powell, for example - though Powell told him he overused the colour in Mean Streets. And Powell was practically a consultant on Raging Bull, giving Scorsese script advice and even guiding him towards releasing the film in black and white. (Again, Powell observed that Robert de Niro's boxing gloves were too red.) Meanwhile, Powell's Tales of Hoffman informed the movements of Raging Bull's fight scenes. "Marty was always asking Michael, 'How did you do that shot?' or 'Where did you get that idea?'" Schoonmaker says. "They shared a tremendous passion for the history of film - but he didn't always go along with Marty's taste in modern film-makers. For example, Michael didn't quite get Sam Fuller. Marty showed him Forty Guns, or started to show it to him, and Michael walked out halfway through. Marty was heartbroken."

The restoration of The Red Shoes came about when Schoonmaker tried to buy Scorsese a print of The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp for his 60th birthday. She was alarmed to discover the printing negative was worn out, and that there wasn't enough money to restore it. Much of the Powell and Pressburger legacy was, and still is, in a similar condition. So she and Scorsese set about raising the cash to fund the restoration. "It's been over two years now of checking test prints and determining how the picture should be restored," says Scorsese. "In restoration circles, very often three-strip Technicolor film can only reach a certain technical level. The colours start to become yellow and you get fringing - where the strips don't quite line up. But the techniques we used here are top of the line. So it looks better than new. It's exactly like what the film-makers wanted at the time, but they couldn't achieve it back then."

Other Powell/Pressburger movies are now in line for restoration, but Scorsese and Schoonmaker's rehabilitation mission does not stop there. For some years, between movie projects (they are currently completing Scorsese's latest, Shutter Island, with Leonardo DiCaprio), they have been working on a documentary about British cinema, in the vein of Scorsese's 1999 personal appreciation of Italian cinema, My Voyage in Italy. Powell and Pressburger will be in there of course; but also Hitchcock, Korda, Anthony Asquith and possibly others we've forgotten about ourselves. British cinema is sorely misunderstood, Scorsese feels, and it needs this documentary even more than Italian cinema did.

Perhaps that's something for next year's Cannes? "Well, I'm still working on my speech [for Friday]," says Scorsese. "I never know what to say. I'm trying to hone it down to my key emotional connection to the film. My favourite scene is the one near the beginning at the cocktail party. Where Lermontov [Anton Walbrook] asks Vicky [Moira Shearer], 'Why do you want to dance?' and she replies, 'Why do you want to live?' Despite all the other beautiful sequences in the film, that's the one that stays in my mind."

Here's an interview with Mark Kermode where Scorsese talks about Powell and Peeping Tom, a film dismissed by the allegedly enlightened Guardian and Observer critic C. A. Lajeune as 'beastly.'

No comments:

Post a Comment